Part 1 – March 22, 2009

Walking down the riverbeds and around the deltas, it is easy to see people getting on with their lives in ways that are covering up the scars of disaster: an ongoing environmental crisis of management. Environmental disaster is made worse by the economic crisis; the poor do not know how they will be next hit, by a returning jobless family member or another typhoon.

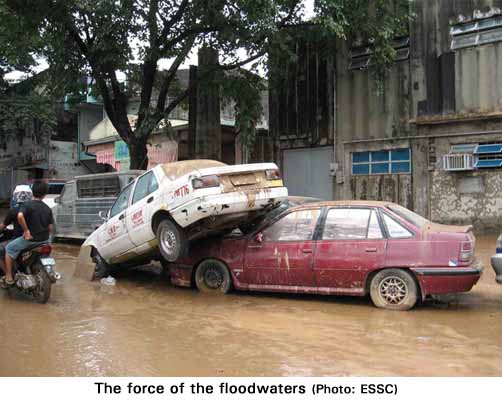

The extremes in both weather conditions and geological events are gaining more focus, brought about mainly by the massive costs to damaged infrastructure, crop and agricultural productivity losses, and tragically, the number of lives lost and those left homeless. Relief responses are stretched more thinly as disaster occurrences are getting more frequent. Rehabilitation and reconstruction responses are facing design and land allocation challenges. The message is getting home that as human lives are connected, so are economies and so too the apparently distinct activities across the landscape; every ‘development' must bear the cost of environmental balancing.

The economic drive by the national government is increasingly focused on a strategy of short-term natural resource utilization with limited focus on long-term sustainability of these resources. Investment opportunities that rely on the nation's raw natural resources include metallic mineral development, river and stone quarrying, agricultural land expansion, plantations, extensive chemical usage for crop protection and fertilization, local wood supply for domestic consumption, marine and fisheries resources, freshwater usage for industries, tourism, and increased office and housing areas.

Whether you are part of the 50% of the world population now living in cities or the 50% left on the land, the environment through heat and water is pressuring daily life in the best of times. The impact of an El Niño and La Niña event in upland and coastal areas and the communities living in these areas demand a response that goes beyond relief. Extreme rainfall events that trigger landslides, mudflows, massive soil loss and flooding are paralleled by extreme droughts that bring about severe losses in agricultural productivity and elevates seasonal hunger in poverty-stricken areas to extended hunger periods for many more.

In climate change discussions preparing for the UN Framework Convention in Bonn 29th March to 8th April, it was recognized that there is a need to have a focus on community adaptation and effective resource management, not simply mitigation. While feats of engineering boost economies and generally secure urban needs, local efforts on a broad scale have to adapt to, rather than control, the flow of nature. People have been adapting in their efforts to survive. Greater support is needed in this for communities to secure a relation with the land and water during times of stress that these stress times do not have to always become a disaster.

Most Asian countries have a difficulty at the negotiation table. For although the carbon print has to be offset primarily by the industrial giants worldwide, the difficulty of such countries as the Philippines is to know critically the amount of carbon we already offset, while at the same time argue that we face the greater problem of the effects of the global change, given the existing poverty and exposure to impact. We have no bargaining power.

Part 2 – November 4, 2009

Activities are now underway for major reconstruction of roads, bridges, communication lines, and other infrastructure. Calls for better disaster preparedness from various sectors were heard anew. Disaster reports and typhoon bulletins hogged national headlines. PAGASA, the government's weather bureau, is getting attention not only in relation to its task of providing weather updates, but also in its oft-repeated request for better instrumentation. Master plans for housing development in Metro Manila of 30 years ago financed by the World Bank are being dredged up and questions are being asked why the recommendations were not followed. The post-disaster impact is seen and felt in crowded evacuation centers, in the outbreak of water-borne diseases, in the calls for protocol review in dam water release, and local governments bear the burden in the massive clearing-up operations required.

Year in, year out, we go through these struggles of re-living disasters brought about by weather and geologic events. We listen to an annual state of disaster address as government and its bureaucracy continue to respond inadequately.

So what has changed now, apart from the new numbers of lives yet again lost to avoidable unfortunate circumstances?

Last 23 October, the President signed into law Republic Act 9729 or the Climate Change Act of 2009. The President also designated a special body chaired by a businessman and a cardinal that will undertake a study of the causes of the recent disasters and look for fresh aid and manage the distribution and disbursement of these funds. Obviously, these national actions were spurred by the recent disasters and questions remain as to whether these will have meaningful impact in the next disasters to come. In the climate change discussions and global deals to be negotiated in Copenhagen next month, the Philippine experience along with other countries similarly situated, is a painful reminder to the rest of the world that the present situation needs to change. Nature is defining how it wants to proceed in the scheme of things and we are part of its definition. For countries like the Philippines, adaptation is our safety net and needs critical support.

Related articles:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web