We went to Broome not only for the 10 days of festival in August but also to stay a while longer to undertake an oral history project with the descendants of Filipino pearl divers (known as ‘Manilamen’) who came to Broome from the early 1880s. We knew from our background reading that many of these descendants are of Filipino and Aboriginal ancestry. What we did not know was that about a hundred years later, Broome would be blessed with second and third wave arrivals from the Philippines. In the 1980s, Filipino women migrated as wives of Australian men and from 2006 onwards, Filipino men arrived as skilled workers under temporary 457 visa contracts.

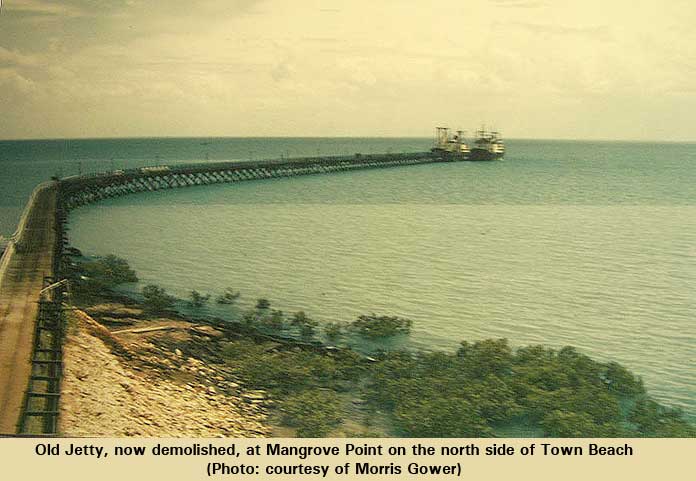

Most Australians are not aware of the 19th and early 20th century Manilamen’s contributions to the cultural and economic infrastructure of Broome. Two Catholic churches were built by Manilamen in the early years, as was the now dismantled Old Jetty. Town Beach, the Old Jetty site, is a place where people gather for picnics, dine at the beach restaurant, swim, or observe at full moon from March through to October, the ‘Staircase to the Moon’ — a visual display of the moon’s reflection on the mudflats of Roebuck Bay that beams like a staircase to the sky.

Filipinos are reputed to be musical. Indeed, the Manila Club established by the first Filipino settlers provided entertainment in town. Under the leadership of a devout Filipino Catholic, Thomas Puertollano, and the guidance of a Cistercian Spanish priest, Fr Nicholas Emo,[1] Filipinos were able to buy land and erect a fine hall. The large Rondalla stringed orchestra they formed was described as ‘one of the finest in Australia.' [2]

Pearl diving, however, was a high risk occupation, and many deaths and injuries occurred. Some gave up diving and took up fishing. The fish traps that were built along the coast by Manilamen gave them an alternative livelihood, and the town benefited from the fresh supply of fish and garden vegetables.

Not only did Filipinos contribute their labour to Broome’s economic foundation as captains, divers, tenders, crew, shell openers and sorters in the pearling industry and later as woodcutters, fishermen and market gardeners. A few, albeit even against all odds, turned out to be successful entrepreneurs. Filomeno ‘Francis’ Rodriguez became a hotelier swiftly rising from his earlier work as crew, diver and pearling master. His descendant, James Frederic Jahan de Lestang told us about the two Broome establishments his great grandfather owned — the Weld Club Hotel and the Continental Hotel. [3]

It would save time if residents in Broome would remember that it is Mr A. Gonzales who is owner of fleet and he is a naturalized British subject and is quite capable of transacting all his business. They would give less annoyance by respecting this position instead of repeatedly calling on me about business matters. Signed Rose Gonzales. [4]

Donatello Costello also succeeded in crossing the colour line. He purchased a town lot in the exclusively white residential area. He would have been able to argue that he should not be classified as ‘Asiatic’ because at the time his native Philippines was a dependency of the United States (from 1898–1935). Consequently, he could hold pearling licences and own as many luggers as he wished. [5]

While pre–Federation Australia had relatively open borders enabling easy entry of foreign workers such as Manilamen into Broome, specific restrictions based on race made life a challenge. [6]

Under the “Immigration Restriction Act, 1901” (commonly known as the White Australia Policy), Asian migration was even more restricted and controlled. After 1902, unnaturalised Asians could not leave and re–enter the country without a Certificate of Domicile (COD). To apply required proof of good character, ownership of property and five years residence in Australia. Certificates of Exemption from Dictation Test (CEDTs) replaced the CODs in 1904 but did not allow families to accompany the certificate holder. Applicants had to correctly write fifty words in a given European language dictated by a policeman or government official. [7]

Historian Julia Martinez writes about the pearling industry’s exemption from the ‘White Australia Policy’:

The pearlshell industry was the only industry to be exempted from the “Immigration Restriction Act of 1901” which prohibited the immigration of colored labor. Pearling masters were permitted to import Asian divers, tenders, and crew under indenture contracts. …For the Australian government, the exemption was ultimately a pragmatic concession to the master pearlers who had threatened to leave Australia if they were denied access to Japanese divers. [8]

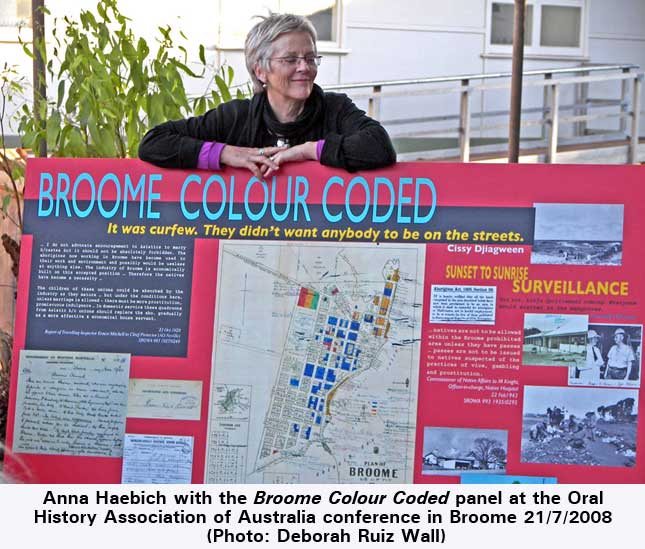

Segregation and race barriers that existed then are starkly illustrated by stories and photographs featured in the Opening the Common Gate exhibition currently showing at the Western Australian Museum in Perth. The Common Gate served as a metaphor for “the different forms of exclusion imposed on the Aboriginal people, including racial, political, emotional, and social boundaries.” [9] It was actually a wire fence running along the municipal boundary of Broome. Initially erected to keep cattle out, the main gate or ‘Common Gate’, as it became known, was located at the highway entrance to the town. However, it was used as a boundary to “regulate the entry of Aboriginal people without work permits, and enforce the exclusion of those classified as ‘natives in law’“. [10]

When we went to the exhibition in Perth, we were struck by the detailed information contained in the “Broome Colour Coded” panel which includes a full–size reproduction of the street map of Broome used by Travelling Inspector Ernest C. Mitchell in 1927. This map had the Inspector’s handwritten notation about the racial categories of the people who lived in the various dwellings: [11]

Mitchell used this information in his report on 23 October 1928 to his superior, A.O. Neville, Chief Protector of Aborigines.

As historian, Christine Choo puts it squarely: “racial and sexual politics converged with the identification by white men of Asian men and Aboriginal women ‘as the common enemy.’” [13]

Such a relationship was viewed as a ‘problem’, precipitating a Royal Commission in 1904 headed by Dr Walter Roth, a former Protector from Queensland. In Queensland, Roth had assisted in introducing legislation to ‘prevent contact between Aboriginal and Asian labourers, and to remove their progeny to institutions.’ The Western Australian government followed suit.

Acting on Roth’s recommendation, Western Australia introduced the “Aborigines Act of 1905” giving legal guardianship for all Aboriginal children to the Chief Protector; making cohabitation illegal between Aboriginal and non–Aboriginal people, any marriage between them now requiring approval from the Chief Protector; and forbidding Aboriginal people from entering prohibited areas around creek estuaries and town boundaries as exemplified in Broome by the ‘Common Gate’. [14]

Despite this legislation, however, life in Broome was not totally restricted. This may be largely due to the fact that white people were still a minority. During Governor Bradford’s visit to Broome in 1904, there were 2000 Asians and only 50 Europeans. [15] Asians and Aboriginal people in Broome today are now a minority in a population of 14,436. [16]

Even during 81–year old Magdalene (nee Ybasco) Van Prehn’s childhood in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Broome was “a very carefree life”, she said. “We used to have Aboriginal friends, Filipino friends, half and half … I feel sorry for my grandkids. They don’t have a free time here (Belmore, Sydney). Those days in Broome, we didn’t care about the future.” [17]

This sentiment was shared by both Sally Bin Demin and Elsta Regina Foy who were born in 1942 and 1937 respectively. On the question of segregation, Sally said, “I can’t think of it directly. It probably happened all the time, I had not noticed. Now I’m seeing it more. At the time, we were the majority. It was our town. If they didn’t like us, too bad. It didn’t worry me. We didn’t care.” But she remembers the imposed seating arrangement at the Sun Pictures where she whispered with her friends, “If you’re white, you’re all right; if you are brown, hang around; if you are black, stand at the back.” [18]

The wonderful childhood memories of the Broome people of Aboriginal–Filipino ancestry we interviewed conjured up a picture of playful innocence and a close–knit mixed–race community who shared their homes, food and songs, and thus felt blessed. However, many of them were evacuated from Broome during the Second World War to Beagle Bay where they experienced another life in an orphanage under the tutelage of nuns and priests within makeshift classrooms where boys were trained for woodwork, carpentry and other job oriented skills and girls for domestic work. Hence, before returning to Broome in 1945, they must have learnt how to survive and adapt to change. Some were separated from their parents when they were moved to Beagle Bay. Their eventual return to Broome engendered a nurturing of a shared community and extended family spirit and a psychological departure from a life that was disrupted and dislocated by the circumstances of war.

And so underneath the tourism glitter of Broome’s turquoise ocean and deep red soil is a history with a rich texture that wove the intertwined experiences of Asian, European and Aboriginal cultures. Hence the question of identity — hardly an issue with the natural poly–ethnic mixture in this town — is sometimes forced by those who insist that people must make a choice, perhaps to resolve Native Title disputes.

Reflecting on the identity question, Kevin Puertollano who has a mixed ancestry of Filipino, Aboriginal, English and Irish, when asked who he thought he was, replied: “My father is a Yawuru man and my mother is from Bard people from the Dampier Peninsula. I’m accepted by Aboriginal people; they call me my bush name … If I feel Aboriginal, if I feel Filipino, that is my right. I can’t help myself. I can’t be anybody else. You are who you feel you are.” If the question comes from an Aboriginal person, Kevin would toss the question back: ‘Do you speak your Aboriginal language? Do you dance your dance?’[19] Broome’s particular mixed–race history has left its people this heritage. For others who are uncertain about the identity of their father or grandfather, a definitive family tree verification remains elusive.[20]

For Shinju Matsuri’s float parade, Kevin constructed a facsimile of a fish trap erected on top of a ten–metre–long truck to remind townspeople that the Manilamen divers of old, some of whom became fishermen, had fed the town with fish picked from the fish traps that they built. Stapled on Kevin’s wires were not just colourful floating cardboard fish but also representative pictures from the first, second and third waves of Filipinos who entered Australia during the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty–first centuries. Along with the Filipino iconic motif jeepney, nipa hut and boat floats, Kevin’s novelty fish trap float design also won a prize from the Shinju committee. Winning the prizes boosted the Filipino community’s pride of tradition in a parade that was somehow reminiscent of a historical cultural dance, this time, between the old and the new.

The three ‘waves’ of people have since met — twice at the Old Jetty site (Town Beach) — to get to know each other, fill in the gaps lost in the memory trail, and hear each other’s stories. The Filipinos seemed to be ‘in a faction’ before this gathering observed Joenna, wife of 3rd wave Filipino Toyota worker, Samuel Fronda, until Kevin Puertollano opened up for them the old history.[21]

Indeed the Filipino story is deeply anchored in Broome’s soil so the new arrivals can hold their heads high and connect with the history of the Manilamen and their descendants. Apart from Filipino heritage the contract skilled workers in the 21st century have another thing in common with the indentured workers of the 19th century — the uncertainty of their tenure in Broome. The Manilamen of the past worked as mariners, engineers, cooks, divers, tenders and shell openers in the pearling industry, forestry, agriculture and construction, while the Filipino contract workers of today are employed as welder, draftsman, chef, landscape designer/gardener, mechanic and electrician in the automotive industry, hospitality, horticulture and now in the cultured pearl industry — skills required in Broome by today’s employers.

Different times, somewhat different jobs, but tides that reached the same shores. After 130 years we have turned a full circle indeed.

ENDNOTES:

ENDNOTES: See also:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web