TIBAK RISING was conceived in 2004 and by October 7th that year, the T’bak group announced its commitment to bring the T’bak Book Project into being and called for submissions from its network by April 1, 2005.

Seven years later the book was launched on July 21, 2012 in the University of the Philippines, Diliman — timed to complement the events commemorating the generation of anti-martial law activists who offered their lives in the struggle against the Marcos dictatorship.

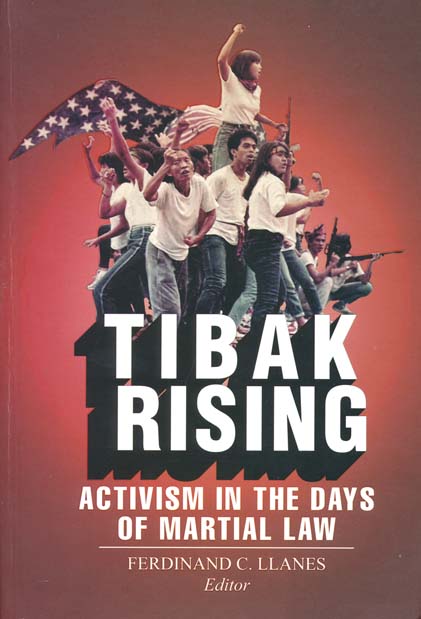

Dr. Michael L. Tan, dean of the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, U.P., a Tibak himself in the Progresibong Kilusang Medikal in the 70s, has the first word in the book’s Foreword: “The etymology of the term Tibak — the syllables of the word “actibista” transposed in the style of slang popular among young people at that time — speaks of a rebellious time.”

And speak they do. The Tibak stories spanning 14 years from the declaration of Martial Law in 1972 through to the EDSA revolt of 1986 (which became known as the Peoples Power Revolution), narrate the experiences of the generation of actibistas who “bridged the movement of the ‘flower generation’/First Quarter Storm with that of EDSA’s ‘Yellow forces’. …It was this generation that bore the brunt of the killings, detention, torture and forced disappearances instigated by the State’s military and police forces. And then, in a twist of deep irony, it was also the generation that had to suffer death and suffering in the hands of its own leadership, an ideological mindset ossified in a schema of dogma and adventurism.”

The book’s editor, Ferdinand C. Llanes, professor of history at U.P. and commissioner of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, and the editorial team of T’bak Inc. have achieved the collection of a slice of history that could so easily have been forgotten. Ferdie explains in his introduction “Memory of a Generation”, that the clandestine way of life under a fascist dictatorship necessitates a self-censoring personality. “Identities were concealed, organizational activities were kept secret, recording or documentation was coded. The secretive nature of activism during Martial Law naturally limited public access to the nuances of day-to-day activist life.”

In the photo albums of many Tibaks you will find no pictures of those very personal events like weddings, children’s birthdays, and family gatherings, because to keep a record of those moments would expose the images of one’s relatives and friends and might put them at risk of interrogation and torture. And yet, close relationships had to form because individual survival is dependent upon the trust of comradeship and collective responsibility.

From the perspective of Marcos’ so called New Society, protest and dissent was presented in the government controlled media as threats to “peace and order”. Then, for security concerns and political reasons, many Tibaks did not want to write about their lives. Consequently, the life and times of the Tibak have been little known. “Thus,” writes Llanes, “the participants must intervene in the retrieval of the past and the recreation of collective public memory.”

Tibak Rising are factual stories that reflect the many-sided dimensions of Tibak experience and highlight the essentials of everyday life rooted in the time and place of martial law and the EDSA uprising. About three-quarters of the text is in English.

In this collection we are treated to more than 40 individual contributors of personal recollections and photos. They are first-person accounts, intimate, rich in detail and drama. Each chapter begins with a collage of photographs and an introduction, arranged under eight themes:

Transitions

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web