THIS YEAR MARKS the 40th anniversary of the imposition of Martial Law in the Philippines. As a fitting remembrance to the lives lost during the struggle against the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos and the equally oppressive hierarchy of the Communist Party, a family memoir came to the fore.

THIS YEAR MARKS the 40th anniversary of the imposition of Martial Law in the Philippines. As a fitting remembrance to the lives lost during the struggle against the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos and the equally oppressive hierarchy of the Communist Party, a family memoir came to the fore.

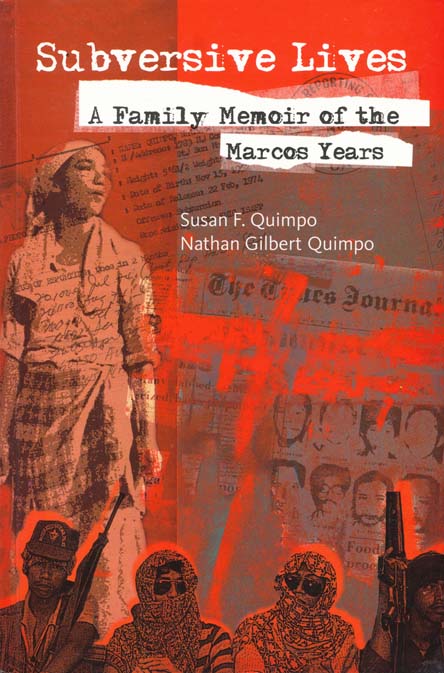

‘Subversive Lives’ is a collection of personal stories written by surviving members of one of the well-known intellectual families in the Philippines that became heavily embroiled in the ‘underground’ organisation and hierarchy of the Communist Party and the National Democratic Front. Spearheaded by two of the ten Quimpo siblings, Susan and Nathan compiled this detailed and moving memoir bringing back recollections from the time when they were growing up in a house not too far from the Presidential Palace.

With fondness, the siblings sew a collage of narrative about the cramped houses they lived in and the neighbours, fruit trees and even a wayward turtle that came across their young and carefree lives. At the other end of the scale, they also bravely recollect the events of overwhelming emotions brought about by the deaths of their hardworking parents, Esperanza and Ishmael, the series of arrests and tortures of family members involved with the revolutionary movement and the disappearance and murder of their two brothers, Jan and Jun.

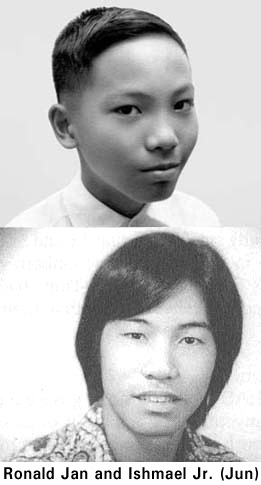

The continuous storm of political and economic marginalisation in the country, triggered the start of social consciousness within the Quimpo brood when their brother Jan, a very bright scholar, dropped out of school and decided to become a full-time political organiser for Kabataang Makabayan (KM), an underground youth group, and eventually, working with the urban poor in Quezon City. Jan was arrested in 1973 and tortured by the military. He was released after a few months with the proviso to report to a military camp on a regular basis. After this horrific experience, Jan continued with his studies and finished his Geology degree at the University of the Philippines (UP) in 1977. In October of the same year, the military raided the Quimpo’s family home in Concepcion Aguila, looking for their brother Jun, who at that time had already joined the New Peoples’ Army (NPA). No one was arrested but two weeks after the raid Jan disappeared, feared to be a victim of military summary execution (‘salvaging’). He was 23 years old.

Another tragedy struck the family with the murder of Jun in 1981. The youngest boy of the family, Jun was recruited by KM at the age of 14. He was initially thought by his older sibling Nathan to be an unlikely person to become seriously involved in the movement. Nathan recalls, “Jun’s extracurricular activities has been mainly devoted to playing volleyball and football, joining San Beda’s church choral group, courting pretty girls and going to parties.” What his siblings thought of as a ‘passing fad’ had in fact accumulated ideological momentum. Jun organised with the urban poor in Constitutional Hills while a student in UP and met Tina, whom he later married in November 1976. A couple of months after, Tina (the younger sister of Etta Rosales, currently the chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights), followed Jun to Bicol and eventually joined the NPA guerilla front.

The discovery of the real story behind Jun’s death dogged the Quimpo family and in particular, Susan. Ten years after his death, Susan was able to speak with ‘Ben’, an NPA supporter who knew of ‘Diwa’ (an alias used by Jun) and ‘Darmo’ (an NPA commander who had gone ‘AWOL’ after being disciplined for womanizing, a serious offense labeled ‘sexual opportunism’ by the NPA). Ben was instrumental in shedding light upon what actually transpired in the days prior to the discovery of Jun’s bullet-ridden body found lying in a rice field in Nueva Ecija. It was the unstable Darmo who chased Diwa to the rice field and shot him seven times, said Ben. Darmo, knowing the severity of his actions and the extreme punishment he would be facing under NPA rules of discipline, later on surrendered to the military. The media feasted on the news of the death of an ‘NPA Chieftain’ and even used a photograph of Darmo (who by that time was known by his real name, Juan Simon) surrendering to General Fidel Ramos the weapon he had used to kill Jun. Juan Simon must have served as a reliable military intelligence as a series of military raids and arrests were carried out following his surrender. However, Juan Simon miscalculated the cunning plan of his former enemies. After a few weeks his family received the news that he committed suicide by apparently ingesting poison while in military custody. Ben remarked to Susan, “That’s what the military does to you when you’ve outlived your usefulness.”

The death of Jun at the hands of another comrade also became the catalyst for his older sister Emilie to rethink her long-term involvement with a wealthy and conservative Catholic group, the Opus Dei. Emilie was a high-ranking pioneer numerary whose graduate studies in Italy was funded by the religious group known for its association with the rich and influential. She and other numeraries had the unique chance to live with Opus Dei’s founding Father, Monsignor Escriva in Rome. It was Emilie (accompanied by her sister Caren and their sister-in-law, Bernie) who collected the body of Jun from a morgue in Nueva Ecija. She experienced first hand the bureaucracy and military arrogance that they had to undergo to identify and claim Jun’s body and give him a proper burial. Disillusioned with Opus Dei’s priorities, and with her other siblings deeply embroiled with the struggle against the dictatorship of Marcos and the military, Emilie began to realise the difficulties in reconciling her vocation with her brother’s ‘selfless and generous commitment to real and genuine causes.’ After a nervous breakdown and two attempted resignations, her personal conviction had gained strength and she finally left Opus Dei in 1982. After 14 years with the group that virtually shaped her young life, Emilie recalls the cold reception that marked her release, “There was no one to bid me farewell in the foyer at Punlaan, as I waited for a taxi to pick me up, with all my worldly belongings in a small suitcase clutched tightly in my hand.”

Another Quimpo sibling that typifies steadfast political conviction is Ryan. Despite contracting polio at seven months old, leaving him with a limp, Ryan didn’t let his physical disability hinder his work for the national democratic cause. A gifted writer, Ryan had been producing a school newsletter at the age of 12 single-handedly. It is no surprise that after being involved in national democratic causes, he became the editor and head of ‘Liberation’, the official publication of the NDF. His physical limitation to attend political rallies especially on the first anniversary of the violent First Quarter Storm was kept in check by his Dad. At 15, he feared that he would not be able to fend for himself if he should leave home and be a full-time activist like his older brothers Jan and Nathan. Out of respect for his Dad and fear of homelessness, he stayed home and missed the rally. As time passed, his handicap didn’t prevent him from being deployed to the countryside to work in the non-guerilla area of Bicol. In the early part of the 80s up to the point of Ninoy Aquino’s assassination on August 21 1983, the anti-Marcos protests came to a political crescendo. Political groups of many persuasions were starting to amass sympathy and perhaps this development catapulted the CPP/NDF to increase its presence overseas by designating an NDF spokesperson in Europe. Together with his young family, Ryan left for France on November 27, 1983 to cultivate the solidarity groups with parallel politics and intentions in Europe.

Nonetheless, doing solidarity and organisational work was not straight cut for Ryan and his family who were not only keeping tabs on their paperwork for political asylum, but also dodging Trotskyites and a suspected KGB agent at the same time. In 1991, personal and political tensions were also starting to appear within the CPP/NDF hierarchy itself. Jose Maria Sison (Joma), the founding chairman of the CPP who is treated as a ‘deity’ by many in the national democratic movement, seemed to be content with the same strategy of the Maoist people’s war that he wrote about in 1970 in his definitive book ‘Philippine Society and Revolution’ (PSR) which has served as a guide on the stages, requirements and strategies inspired by the revolution in China under the leadership of Mao Zedong. During a meeting in Holland, Ryan asked Joma if the ‘protracted people’s war’ he prescribed for the Philippines is still applicable given its political situation and that perhaps Joma needed to update his theory. In response, Joma was indignant and allegedly lost his temper. Ryan recalls, “He raised his voice, saying that there are fundamental things that remain unchanged.” After the release in January 1992 of the draft document “Reaffirm our Basic Principles and Rectify the Errors” that eventually lead to the split within the national democratic movement, Ryan resigned from the revolutionary movement and wrote in his letter to the Central Committee that “the time for waving [Mao’s] little red book is over”.

Nathan, Ryan’s older brother, fled the Philippines in January 1990 to seek political asylum in the Netherlands after the military put a P250,000 reward for his capture. Nathan was briefly assigned as the OIC (Officer-in-charge) of the NDF International Office in Utrecht. He was initially hopeful that disagreements within the CPP’s Central Committee would be resolved when the door for discussion opened to pave the way toward a second party congress. Unfortunately, Nathan’s optimism did not translate to reality and, in September 1992, he was expelled from the CPP after being tried by a ‘kangaroo court’ for various trumped-up charges. To further vilify other party dissenters, Joma sent faxes to the Philippine Daily Inquirer and named Central Committee members Ric Reyes, Rolly Kintanar and Benjamin de Vera as “renegades and counter-revolutionaries”. The ideological split within the party reverberated throughout all underground and legal organisations associated with the national democratic movement. The two main divisions became known as the RA (‘Reaffirmists’, those loyal to Joma) and the RJ (‘Rejectionists’, those who question Joma’s leadership).

In retrospect, the earlier and well-known party error of the ‘boycott’ movement in the 1986 Snap Election failed in comparison to the impact it created to the advancement of the interests and causes of the national democratic movement. The refusal of Joma and his supporters to adapt to an applicable strategy has caused distrust and alienation between many well-meaning activists. But the most heart-breaking revelations came about when the division also opened a flood-gate of blunders committed by the party. Between 1982 to 1990, a series of military campaigns against suspected deep penetration agents within the movement were carried out. In one campaign alone that took place in Southern Luzon, 66 were killed and 46 were tortured.

Although the general tone of Subversive Lives is intensely political, it also exudes an almost surreal humour on living underground. Ryan recalls the UG house with a surprisingly big kitchen sink that he and his young family rented. He later discovered that the place used to be a morgue and the king-size sink was used for washing dead bodies. Equally amusing was an occasion at the height of UG house raids when young children of kasamas innocently made paper planes using subversive materials and played with them in the streets for all to see. And of course, the comical waddle of a young female activist who turned ‘full-time’ and wore ten layers of underwear as she could not pack everything in her bag which would have otherwise called her mother’s attention.

Like many activists, the Quimpos were also susceptible to the guilt of losing parents while fully engrossed with risky political work that required them to be in constant military surveillance. In particular the death of their father, Ishmael, in 1977 from his bout with cancer made the siblings retrospective of their family obligations. Susan succinctly reflects when she received the news of their father’s passing, “When does the ultimate sacrifice of one’s family and one’s personal dreams for the sake of revolution and country cease? When myself and family hold precedent over one’s love for country?.” Hardened by political struggle throughout his adult years, Nathan in his recollection of the burial rites gave the readers a glimpse of the emotion embodied by the memory of his disciplinarian father’s argument at the Cervini carpark over his involvement in student activism in Ateneo. Nathan was still incarcerated in Crame at the time and had to be fetched to attend the funeral but remembers the feeling of consuming sadness, “Walking back to Marlene’s car with the two guards, I looked up. Cervini Hall stood in the distance, atop the hill. I quickly turned away as I felt something ache deep inside me.”

The lives of the Quimpos are intricately woven through the politics of the Marcos dictatorship as well as the fundamentalist leadership of the Communist Party. Of the ten siblings, seven were involved in the revolutionary movement, five were arrested and detained and two lost their lives. By the mid 1990s, all the Quimpo siblings had disassociated themselves from the revolutionary movement. One can only imagine the emotional courage of each as they bare their innermost thoughts to recall and relive the past to provide us an intimate glimpse of what they have endured while traversing their extra-ordinary lives. Subversive Lives is a memoir of a courageous family who faced remarkable challenges with solemn determination to do what is right and just in a society desensitised by the constructed culture of oppression.

Related Article:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web