IN THE BEGINNING, there was a soup bone, bleached by rain and sun, near the wall of the prison grounds in Camp Olivas, Pampanga. I don’t recall who the first prisoner was who picked up the soup bone or why he thought of rubbing it repeatedly against the rough cement wall; it could simply have been his way of releasing extra tension. Anyway, the rough cement eventually ground the bone into a flat oval shape. Then he pried a nail from a discarded plank and used it to bore a hole through the bone.

How that first bone pendant got to me, I can’t recall anymore, but it must have been sometime in 1975. The bone came with a request: “Can you paint something on my bone pendant?” I was in solitary confinement then, as punishment for leading a hunger strike to protest torture. Except for the isolation, the three months were not as harsh an experience as portrayed in movies. To help me pass the time, I asked for acrylic paint, paint brushes, and small clay pots; my mother (who was the only one allowed to visit me twice a week) was permitted to buy them for me. Most mornings, faced with another long boring day, part of my plan for surviving the day included deciding on the number of clay pots I would finish painting with ethnic patterns.

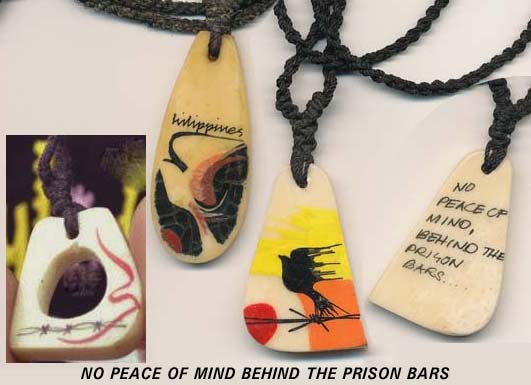

The first image that I painted on the bone pendant was a clenched fist, breaking free, with a broken chain attached to the wrist; predictable prison art.

After a few more bone pendants, the image I usually painted was a bird struggling to be free. To fit the bird into the long oval shape, I drew the bird in side profile. Thousand of pendants later, this became one of the key symbols of prison art.

When our group of prisoners was transferred from Camp Olivas to Fort Bonifacio, I heard the story about the first pendants made there. Instead of bone, they were made of wood, sawed from the branches of a tree that had been planted by William Pomeroy who spent some of his prison years there.

I think it was our group from Camp Olivas that brought the idea of bone pendants to Fort Bonifacio. The prisoners there were much more settled and more organized. In fact they had planned an ambitious mass escape that had been foiled. They decided to systematize the production of prison pendants.

We adopted a similar system of producing prison pendants when we were transferred to Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan.

The first step was boiling the soup bones, which had been bought by prison guards who did the shopping based on a list provided by the prisoners. This and similar arrangements in other prison camps were usually the result of protest hunger strikes. We asked the guards to pick bones that still had some meat and bone marrow, which were cooked with cabbage and pepper.

The next step, after the bones had dried, was sawing them into shorter sizes, which were then split into smaller pieces. The next step needed more skilled work – grinding the bones to different shapes and sizes. At Fort Bonifacio, the authorities agreed to the prisoners’ request for motor-driven grinders. Visitors would be taken aback by the sight of the grinding team with face masks, their hair clouded with fine bone powder. Another team used hand drills to bore holes in the pendants.

The shaped bones were passed on to the team of artists. We painted the different images, and coated them with transparent nail polish. The final step was to distribute the painted pendants to a larger workforce who made the macramé nylon necklace with a clasp.

Our group of prisoners were ordered by the military tribunal to be transferred back to Camp Olivas. We continued producing on a smaller scale, and since we were all part of the Left, we initially agreed that in the spirit of solidarity, we would adopt the “communist” principle of “from each according to ability, to each according to need.”

That sharing arrangement did not last very long. Many of those who had more ability had very little need, while others in greater need had much less ability. After a while, those with greater ability but very little need lost their motivation. We had to accept that we had overestimated our sense of solidarity.

Logically, the next step was to slide back to the “socialist” principle of “from each according to ability, to each according to work.” But this rewarded those who were quite skilled, to the disadvantage of those who were much less skilled. Eventually, we settled on a “mixed economy,” incorporating the idea of “work points” from China.

The pendants we produced were sold for 15 pesos. We distributed this income across three categories: 1) Capital replenishment; 2) Work points: cooking, sawing, splitting, grinding, painting, polishing, stringing; and 3) Common fund.

I don’t remember the exact amounts, except that the contribution to the common fund was 20 percent of the gross. What was it used for? The common fund was used to subsidize the transportation costs of families of poorer prisoners, and also their emergency medical needs. But part of it was placed in an “escape fund” which was administered by a special committee.

In its early interpretation, this led to ambitious and failed plans for the mass escape of a whole prison population. Later, the policy had a more flexible interpretation. Those who had reasonable prospects of being released through legal process or negotiations were encouraged to pursue that course. Being a priest, I was presumed to belong to this category. Those who thought they would have no such chance or who wanted to get out sooner, could plan individual or small group escapes. No more mass escapes.

If any prisoner had an escape plan, he or she could present it to the escape committee, and justify a request for budget support, which could go up to a few thousand pesos. I was told about some prisoners who did manage to escape, even if only after repeated tries and repeated budget requests. But that’s another story.

So from time to time we would get word from the prison leadership that we need to increase our production and earn more in order to replenish the escape fund. The irony is that the successful escape of prisoners, or even the release of prisoners tended to conflict with our production schedules and targets.

After any successful escape, there was an automatic, though temporary, clamp down on visits from our relatives, which cut us off from the people who took care of buying our supplies and bringing our products to the markets.

From time to time, there would be mass releases of prisoners, and they of course included some who were either highly skilled, especially artists, or those whom we had trained for various phases of the production of pendants and other prison craft. Those of us who were left behind were happy for them and even escorted them with rousing songs to the prison gate. But after that, production would stop for two weeks, as the people who were left inside yielded to some understandable depression. And those of us in charge of production teams had to worry about how to train a new set of workers.

During one of those production lulls, we reflected on the peculiarity of our production system in prison: “Our labor force is recruited by the government, when the military arrest them. We are not asked what kind of skilled workers we need.”

Another prisoner pursued the point: “And it is government that decides to take our labor force away, often just when we have trained them, by releasing them from prison.” Still another pushed the weird logic further: “Why don’t we give the military arresting units a list of the priority skills we need for our prison production?”

Of course the government remained unaware of our needs, just as they remained unaware of the true purpose of our innovative prison industry.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web