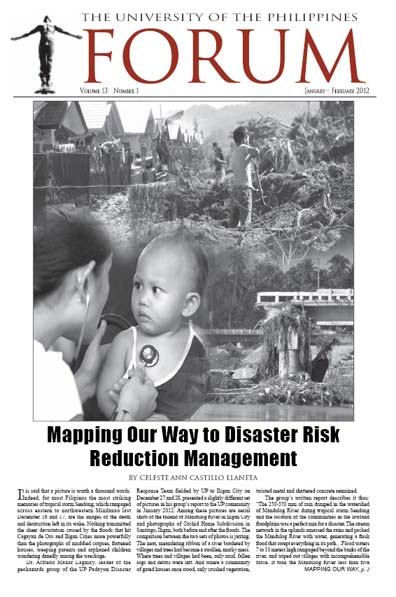

Where trees and villages had been, only mud, fallen logs and debris were left. And where a community of gated houses once stood, only crushed vegetation, twisted metal and shattered concrete remained. (Orchid Home Subdivision in Santiago, Iligan)

The Geohazards Group of the Padayon Disaster Response Team fielded by the University of the Philippines to Iligan City on December 27 and 28 describes the scene of devastation thus:

“The 250-350mm of rain dumped in the watershed of Mandulog River during tropical storm Sendong and the location of the communities in the lowland floodplains was a perfect mix for a disaster. The stream network in the uplands amassed the rains and packed the Mandulog River with water, generating a flash flood that swept everything in its path… Flood waters 7 to 10 meters high rampaged beyond the banks of the river, and wiped out villages with incomprehensible force. It took the Mandulog River less than five minutes to fill its floodplains, land which people appropriated for themselves.”

“Human” disasters

The definition of disaster has undergone shifts over the decades.[1] Up until the 1970s, the dominant view was that disasters and natural events such as earthquakes, typhoons, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis were all the same. Disasters were acts of God, unavoidable and inevitable, and for many governments and international agencies, the emphasis was on responding to such events, and perhaps ideally preparing for them. From the 1970s onward, interest grew in implementing ways to mitigate losses through physical and structural measures, although physical mitigation efforts have been minimal in many countries.

In the 1980s and 1990s, social scientists and researchers in the humanities revealed that the impact of a natural hazard depends not only on the physical structures, but also on the capacity of people to absorb the impact and recover from loss or damage. The focus turned toward social and economic vulnerability, and to the developmental processes that generated different levels of vulnerability. Vulnerability and risk reduction emerged as a key strategy in reducing the impact of disasters. After the 1990s, risk management and reduction became the standard paradigm on the premise that every single human development activity has the potential to increase or reduce risk of disaster.

In short, nature doesn’t create the disaster; humans do. A typhoon occurring over a desert island is a natural event. A typhoon occurring over a highly populated area, destroying houses and killing hundreds, is a disaster. “Essentially, disasters are human-made,” writes Emmanuel de Guzman, consultant, Asian Disaster Reduction Center and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs-Asian Disaster Response Unit.[2] “A catastrophic event, whether precipitated by natural phenomena or human activities, assumes the state of disaster when the community or society affected fails to cope. Natural hazards themselves do not necessarily lead to disasters. Natural hazards…translate to disasters only to the extent that the population is unprepared to respond, unable to cope, and consequently, severely affected. The vulnerability of humans to the impact of natural hazards is to a significant extent determined by human action or inaction.”

With typhoon after typhoon battering the country and wreaking havoc on lives and property, the sheer repetitiveness of it all has become a source of frustration for many. “[We have seen this happen] over and over again. Same problem; only the places change,” says Lagmay, who heads the Volcano-Tectonics Laboratory and Environment Monitoring Laboratory of the UP National Institute of Geological Sciences. “And the way we treat this is: [the disaster] happens and we respond. It’s all over the media, and we’re all concerned. But in the interim, in between disasters, not much attention is given to [preparing for it].”

This predominantly reactive manner of dealing with disasters is part of the old paradigm for disaster. And this is not limited to the Philippines alone. “In the 1990s, disaster risk management was more about post-disaster relief and recovery, and there wasn’t much thought given to what could be done to prevent and reduce the impact of disasters,” Abhas Jha, the World Bank coordinator for disaster risk management in East Asia and the Pacific, was quoted in an article published in Development Asia in March 2011.[3] “Now, governments are much more focused on prevention and risk reduction. Finance and planning ministries are recognizing the benefits of investments in disaster risk reduction.”

“Disasters are now viewed as a product of failure in development planning,” says Lagmay. “If we know through science and technology where the hazard areas are, and you let people develop in those areas and allow the population to grow, the event that will happen in the future will bring forth a lot of damage, and that is precisely the kind of disaster we want to avoid.”

The letter of the law

The Philippine national government has put in place laws that aim to steer the country toward disaster preparedness and risk and reduction management. Such laws include Republic Act (RA) No. 9729 (Climate Change Act of 2009) and RA 10121 (Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010).

In fact, during the United Nations Settlement Program’s 6th Asian City Journalists Conference held last October 2011, Prof. Rajob Shaw of the International Environmental and Disaster Management Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies at Kyoto University praised the Philippine disaster response model as one that must be replicated in Japan and elsewhere in the world. Among the points he singled out were the calamity fund (known under RA 10121 as the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Fund, which is a minimum of five percent of the estimated revenue of a local government unit); the high visibility of the Philippine president during relief efforts which could stimulate national and international assistance; and the extent of youth participation in pre- and post-disaster relief operations, as in city-planning and decision-making. The bad news according to Shaw is the lack of specific mitigation projects in the Philippines in post-disaster setting and the lack of efforts to change the mindset of the people—such as the people’s stubborn refusal to leave their houses and belongings even under threat of being swept away in a flood.

Then Sendong happened, with almost the same results seen before in Metro Manila with Ondoy, in Northern Luzon with Pepeng, and in Pampanga and Bulacan with Pedring and Quiel. Accusations flew, with national disaster response officials blaming the indifferent, complacent public who refused to evacuate even when warnings had been issued,[4] and the public blaming their incompetent, negligent and shortsighted local government officials for worsening the situation.[5] Finger-pointing aside, it is apparent that somewhere in the chain of implementation from national government and its agencies, to the provincial governments, the city governments, the municipalities and barangays and finally the citizens, the concepts of disaster preparedness and risk reduction got lost along the way. …

The lay of the land

From the aerial views of Iligan City and Cagayan de Oro City before Sendong, with the pictures of entire villages located where they should not have been, it is easy to see where exactly urban development had gone wrong. Hindsight is 20/20, after all. But according to Lagmay, foresight can also be just as clear — and amazingly empowering for barangays and individuals alike. All that it would take is a shift in consciousness and a little help from another visual tool: the barangay-level geohazard map.

Geohazard flood maps, such as the simulated flood maps available for free at http://www.nababaha.com, indicate areas in the entire Philippines that have a high flood hazard (floods can reach a possible height of over 1.5 meters), a moderate flood hazard (0.5-1.5 meters) and a low flood hazard (0.1-0.5 meters). Such maps are based on the topography of the land and land use features, with data processed using software such as Flo2d, a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-approved flood routing application software, and thus serve to identify the country’s many watersheds.

… According to Lagmay, the DoST [Dept. of Science & Technology] now has invested P1.6 billion in a project that aims to generate high-resolution topographic maps all over the Philippines – maps that are far more detailed than even Googlemaps, with its resolution of 1 meter or less. “We’re talking about 25 cm resolution, with elevation. From that kind of topographic map, you can do simulations of different kinds of rainfall events.” This, he adds, is one way of harnessing science and technology to help save and improve lives and prevent disaster. The maps will be generated using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology, and will be disseminated to as many people as possible – individual citizens and local government units both – through the Internet. Citizens can even demand to see their barangay or city geohazard map from their local government officials.

…”The first step [in reading this map] is to know you’re in a hazard area,” says Lagmay. “Once you know that, you, the individual can do something. You can ask your barangay captain, ‘What is our evacuation plan? Where do we go? Where is our relocation site? Why aren’t we conducting safety drills?’ [This way], this knowledge [of disaster preparedness] will become part of our system and culture.”…

Assessing vulnerability

Maps also feature in the Vulnerability Assessment Tool, a newly developed instrument of the UP-SURP to aid provincial LGUs in mainstreaming climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in their land-use and development plans. …By integrating such a vulnerability assessment into its development plan, a province could take into consideration things such as future projections of hydro-meteorological conditions; situation analysis for future scenarios and future issues and challenges; land use and resource development and management plans including locations where development must be constrained and locations for more potential development; priority development and management programs; and priority investments.

“You will not be able to separate climate change adaptation from disaster risk reduction. Disaster risk reduction is short-term; climate change adaptation is long-term,” says Delos Reyes.

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web