by Dee Dicen Hunt

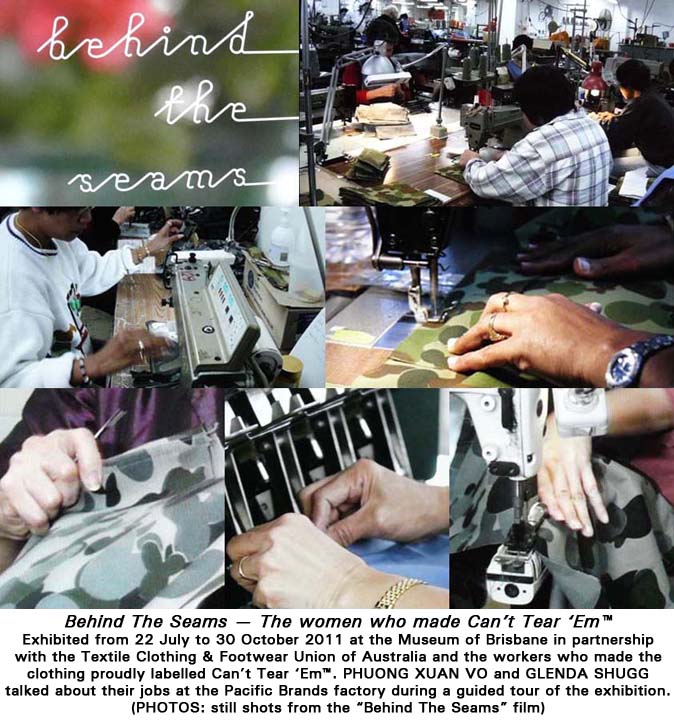

As well as samples of the Can’t Tear ‘Em™ workwear and panels of Marisol Da Silva’s photos with quotes from the garment workers who made them, there is also “Behind the Seams” a 15-minute film produced by the Museum of Brisbane and the TCFUA (Textile Clothing and Footwear Union of Australia).

For me, that day’s exquisite coincidence was meeting Phuong Xuan Vo and Glenda Shugg, two of the women who had worked at the Brisbane factory. They just happened to be there at the museum before going on to the Brisbane Writers’ Festival for a presentation with chef Mark Jensen about food and community. Of course I took the opportunity to chat with Phuong and Glenda and discovered I had missed their guided tour of the exhibition in August, but there was to be another scheduled in five weeks time. We exchanged email addresses and I attended the next presentation on October 16.

Phuong Xuan Vo came from Vietnam with “the boat people”. She had lived in a refugee camp in Thailand for one year and seven months, arrived in Australia in 1990, studied English for three months, then soon got work because she is a trained dressmaker. In 2002, she was employed as a machinist at Can’t Tear ‘Em and worked there for seven years until the factory’s closure. Phuong is presently completing a course in hairdressing.

Glenda Shugg migrated to Australia from the Philippines 32 years ago. She worked at the Can’t Tear ‘Em factory as a machinist for eighteen years from 1991 until its closure in 2009. Glenda is from Davao City in Mindanao.

At the October talk, Phuong and Glenda described how the production line worked to assemble components into a finished garment ready for packing at the end of the line. If you’re not working on the line, you might be making pieces like pockets, cuffs, collars, buttons, button holes or the yoke. “And we don’t sit down, we stand up,” said Glenda.

“Our production of finished garments per day could be 400 to 600 depending upon the garment. But, for the army jackets, you can only do 200 per day. They are really difficult because of the amount of stitching required,” said Phuong. She really liked working on the hi-vis safety vests because they are easy and she could exceed her production quota.

The eventual introduction of a ‘just-in-time’ management system, designed to eliminate waste, increase productivity and achieve completion and delivery by a determined date, put greater stress on the line to maintain quality. “If you make a mistake you have to unpick and it’s easy to make a mistake because you are making garments of different size,” said Phuong. You need to concentrate and be organised. “You can’t always make perfect,” Glenda added. “If you have to unpick it wastes a lot of time. You need to take care with the shoulder pieces, that both left and right sides are the same size and sometimes we have to recut them.”

But there was more to appreciate in the Can’t Tear ‘Em factory than turning out a well made garment and meeting quotas and deadlines. The women became very close friends. Glenda and Phuong talked about social life in the factory:

“Sometimes we go out together, sometimes we bring food inside the factory, sharing different kinds of food. We had many different nationalities working there – Greek, Philippine, Vietnamese, Chinese, Indian, New Zealander, Australian, Polish, Italian, Lebanese…”

“We always celebrate at Xmas time and New Year. We bring a plate, we eat and share together, very happy. One New Year everybody wore a red shirt or red dress.” “And for breast cancer research we wear a pink ribbon, we do that too. If someone’s kids are doing a school project, the mothers distribute a leaflet and we give them a contribution. And with so many languages spoken in the factory, sometimes we have to help each other understand the jobs that are required. We’re always happy to help each other. That’s why we are very close together.”

On the day of the factory’s closure, 24 July 2009, the workers organised a restaurant luncheon and Glenda’s camera caught the emotions of saying ‘goodbye’ in the coach that took them back to the factory for the last time. Twenty months later they organised a reunion lunch. The “Behind the Seams” film shows the spirit of friendship and community that grew in their workplace and continues to this day.

“For me,” Phuong said, “the Can’t Tear ‘Em factory was like family, no matter what problems we have, we share. Most of us are women, only two men work with us, so we all communicate — as women do. Since the closure of the factory some still have not found jobs, others have found different jobs, not sewing.”

“Like me,” said Glenda. “I’m only on call in a different job. I’m not young any more so probably that’s why it’s hard for me to find a full-time job. I miss working. I’ve been working since I was 18 years old in the Philippines, and now suddenly, no work. It drives me crazy staying at home, it’s so boring. I like to work. It’s nice to have a job, it’s nice to have your own money.”

“Right now I’m studying hairdressing and working, so I’m happy,” said Phuong. “But every time I see a uniform that we made, I think of the factory and miss everyone. When I started working with the museum, I was very nervous. The union asked us to come here to the museum because there was a job to do.”

As Cultural Liaison Officers for the museum, Glenda and Phuong were at the core of contacting everyone for the exhibition, planning and helping put it together. The idea for the exhibition came out of the projects the TCFUA is doing in other states. It is part of a national series of arts projects acknowledging the contribution of textile workers at the seven Pacific Brands sites which closed manufacturing in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria.

In February 2009, both the TCFUA and the general public were shocked when Pacific Brands announced that 1,850 people would lose their jobs. It was a devastating blow to the workers, their families and the industry.

By May 2009, the union in consultation with the workers, most of whom are migrant women with long years of service, successfully negotiated an agreement with Pacific Brands to provide training advocacy and support to all those retrenched.

Just like a well made garment, the making of the “Behind the Seams” film could not have happened without its cast and crew. From the closing credits of the film, they are:

Curator/Producer: Christine Dew

And, not to be forgotten are the exhibition photographs by Marisol de Silva and the graphic design by Studio Pounce.

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web