In the 1960s U.S., physicians commonly addressed female patients as if they could not understand medical diagnoses, and sometimes withheld information about their illnesses; unmarried women could not legally get birth control; women who sought sterilization had to qualify by fitting an arbitrary formula (number of children x patient’s age = >120*), while poor and minority women were sometimes sterilized without their knowledge, let alone consent; women were routinely excluded from clinical trials of important drugs; women discussed breast cancer in whispers with a sense of shame. A dominant nationwide hypocrisy pretended that sex fits only in marriage; most gays and lesbians had to dissemble when seeking health care; Americans mostly believed that whole milk, red meat, cheese and butter were fundamental to a healthy diet, and took our children to McDonalds when we lacked time and money.

In this medical landscape, the achievements of the women’s health movement are impressive: Improvements in breast cancer treatment, women’s control over childbirth, the number of women doctors, the information that physicians give patients, the women’s health centers, and manuals that discuss women’s sexual pleasure as well as men’s. But few understand that these gains didn’t just happen, a part of scientific and social progress. They were the hard-fought products of a social movement.

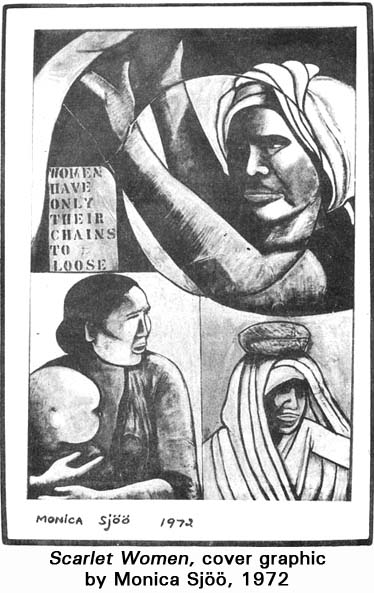

Even less well known is that Our Bodies Ourselves helped mobilize women activists throughout Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe, where they are often the most progressive forces in the field — anti-war, anti-fundamentalist, anti-neoliberalism, pro-human rights.

Like many social movements, Our Bodies Ourselves has an origin myth, a Cinderella story of triumph from modest beginnings: In 1969 at a conference of Bread and Roses, a Boston-area socialist-feminist organization, a group of women came together in a workshop to vent their frustrations with sexist and arrogant physicians. Continuing to meet weekly, they planned to create a kind of “Angie’s list” of good and bad doctors, but as they collected scores of patient reports, they decided that a broader educational project was needed if they were to become educated and confident enough to resist the intimidation that came with sitting on examining benches, covered only with paper wraps, addressed as “Cindy” or Aisha” by Dr. X.

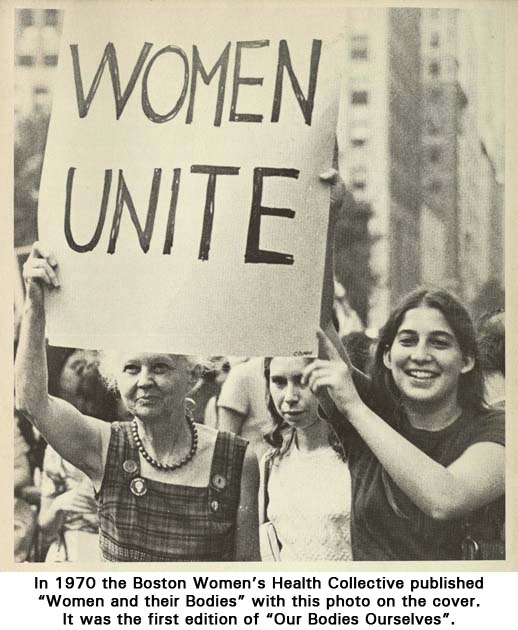

In 1970 they produced the first Our Bodies Ourselves. Titled Women and their Bodies, it was printed on newsprint and distributed by a small New-Left non-profit, the New England Free Press, and sold for 75 cents. Some pages were ink-smeared and its 194 pages were numbered by hand. Even without advertisements or commercial distributor, the book sold 250,000 copies, the demand overwhelming the Free Press.

This word-of-mouth swell of interest was propelled by a mass social movement. The group that wrote the book, part of Bread and Roses, a Boston-area socialist feminist organization, emerged from consciousness-raising, the vibrant organizational tool invented by the women’s liberation movement. The radical content of the book would have been inconceivable without the civil-rights/new-left/feminist context. With detailed line drawings of genitalia, complete with pubic hair and the variety of hymens women might have; a discussion of sex that presented heterosexuality, lesbianism, masturbation and celibacy as equally valid choices; a section on abortion that told the reader where to go to get one, illegally in Massachusetts or legally abroad, and estimated the costs of these options — this was not your standard Left-wing political pamphlet.

Our Bodies Ourselves was not a book of lessons in how to be healthy. It was a political and an oppositional intervention. It challenged not only the culture of medicalization and the sexist arrogance of some doctors but also the pharmaceutical companies, the absence of safety regulation, the global political economy of health care. Its impact was possible because a large women’s health movement was challenging the whole health industry: by 1973 there were 1200 women’s health groups in the U.S. providing services and education and agitating to democratize mainstream health care; many of them worked together through the National Women’s Health Network. This movement exposed the dangers of high-dose birth control pills, sued one of the big pharmaceutical companies over deaths and injuries from the Dalkon Shield IUD, forced the adoption of federal regulations against sterilization abuse, persuaded the Centers for Disease Control to study toxic shock syndrome, developed a model law guaranteeing patients’ access to their medical records. It was the women’s health movement that forced a randomized clinical study of hormone replacement therapy; the findings, reported in 2002, showed that the risks outweighed the gains. (Now the data show that many women probably developed breast cancer because they took the hormones that physicians and drug companies pressed on them.)

The authors decided they wanted the distribution that a commercial press could provide (the individual authors earn nothing from sales of the book). Published by Simon and Schuster, it became a NY Times best-seller. High school libraries often could not keep up with how often it was stolen by teenagers desperate for its contents but embarrassed to check it out. Worldwide it has sold well over 4 million copies (its various versions, some of them unauthorized, and its multiple distributing channels make it impossible to get an exact count) in 22 languages from Spanish to Albanian to Telugu, with versions in seven more languages in process.

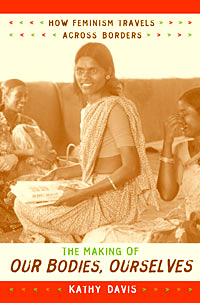

In other words, the book has had marathon legs. Now feminist scholar Kathy Davis has written a thoughtful analysis of its global travels, arguing that what enables it to cross so many cultural dividing lines is not just its information but also its radical method. This method, a democratic politics of knowledge and expertise, should be attended to both by theorists and by anyone interested in grassroots social change. Yet as Davis points out, few of today’s feminist intellectuals would identify Our Bodies Ourselves as making a contribution to feminist theory or, I would add, to organizing strategy. Disclosure: In 1996 sociologist Barrie Thorne and I reviewed Our Bodies Ourselves as one of the ten most influential sociology books of the previous 25 years, for a silver anniversary issue of Contemporary Sociology. Most of the sociologists we heard from thought our choice was nonsense, that the book was a practical manual, not a work of sociological scholarship. Their judgement arises, of course, from how one defines sociology and scholarship.

When she turns to how Our Bodies Ourselves was made and remade, however, Davis’s discussion is both astute and penetrating. The genius of the women’s liberation movement of the U.S., in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was what came to be called consciousness-raising (CR) groups. When they worked, these were not therapy or support groups but investigations of how gender and women’s subordination were maintained – culturally, socially, economically, politically. These small groups created a free space in which women gained the collective confidence to challenge authoritative prescriptions on the nature of woman by religious leaders, lawmakers and physicians. CR operated on the premise that, despite our acculturation into the same gender standards as the men of authority, we could try alternative explanations of, say, why women were nurses and men were doctors. CR groups developed oppositional interpretations of our experiences, and Our Bodies Ourselves continued that process with a focus on health.

The limitation on this process, of course, is that CR groups, including the group that produced Our Bodies Ourselves, and the readers who responded to the book were relatively homogeneous in class, in race and in nationality. So for the book to communicate internationally, it had to avoid assuming that bodily experiences are universal. Davis begins by explaining this challenge, without surrendering the premise that respect for reported experience remains a basis for building knowledge democratically. The catch is, the experiences (plural) must be diverse enough to understand where difference and inequality impede democratic activism.

The original authors of Our Bodies Ourselves would be the first to acknowledge that they did not set out with the lucid strategy that Davis lays out for the reader, that they improvised their way. An early example of the authors’ naiveté about how to spread their work resulted from the first commercial-press contract they signed, with Simon and Schuster in 1971. They were tough negotiators and what they were able to get shows what a hot property the book was: complete editorial control over all text and photographs; making books available at 40 percent of cover price to all non-profit women’s health groups; and a simultaneous Spanish translation for distribution within the U.S.. But Latina activists who tried to use it found that this literal translation did not fit the needs of U.S. Latinas. The book was saturated with the perspective of educated, middle class white women. In fact, the group’s initial chutzbah [audacity] in challenging medical authority was partly a product of their privileged educations and class and race positions. Working through this conflict shifted their understanding of “translation,” an understanding now argued in theory by some scholars but learned through experience by the Our Bodies Ourselves collective: Translations have to betray the original in order to be faithful to the project. Words and sentences have different meaning in different contexts. Besides, the point was not only to communicate counter-facts to challenge the facts women learned from moral authorities in their culture. The objective was also to challenge authoritarian relationships. What was oppositional and radical for the U.S. authors, such as challenging mainstream medical authority, made no sense to women who lacked access to medical care. Translation was not mainly a linguistic operation but rather a holistic political practice, and it required being embedded in the situation of the readers.

We should not imagine that, in these global discussions, American feminists were necessarily more “advanced.” In some cultures, and not only the European, women were accustomed to speak of sex more frankly than Americans did. (Bawdy jokes among women are common, for example, in many conservative Muslim cultures.) Germans thought the book too focused on motherhood; several Third-World women’s groups thought the Americans did not grasp the global economy of health. Often the Americans contributed most by rounding up foundation money for translations.

Kathy Davis, replicating in her book the method she analyzes — illuminating theory through studying experience — shows us this process of translation in two cases, well chosen because on some points they created opposing adaptations. One translation, creating Nuestros Cuerpos, Nuestras Vidas for Spanish-speaking Latin America and North America, took more than two decades. The translating group changed, of course, the experiential accounts and the illustrations to reflect Latina’s lives. This was just the beginning. They also thought the language needed to be more poetic, not only for literary reasons but because of the oral traditions of many who would hear but not read the book.

The American book began with a discussion of body image and the yearning for a perfect, sexualized body, pressures the Latinas blamed on a commercialized, wealthy, and individualistic culture. Distress about body image was not a major concern in Latin America. Their first chapter, instead, was “Perspectiva Internacional,” discussing issues the Americans put in the last chapter: the problems of poor women deprived of resources yet responsible for family maintenance, problems created by imperialism and global corporate power. A chart reports educational levels, contraceptive use, maternal mortality (8/100,000 in the U.S., 650/100,000 in Bolivia) and other social indicators across the Americas. And yet, the first sentence in this chapter reads, “As feminists, we feel a close bond with all women.” [Como feministas, sentimos un vínculo entra able con todas las mujeres.] In other words, a strong assertion of some universal common interests. In other words, while they expunged the book’s U.S. and middle class assumptions about women’s resources, they nevertheless saw global cooperation as the basis for their work.

One of the most sex-radical images in the book, a woman alone in a room looking at her vagina and cervix in a mirror, made no sense to them, because it assumed the book would be read by an individual privately. The Latinas wanted to reach women who could never buy the book and hoped for its use in group educational meetings. Above all they disliked the self-help emphasis of Our Bodies Ourselves, which oozed the individualist, private solutions offered in America’s fitness and health craze. They banished the words auto ayuda and used ayuda mutual.

The Latinas also thought it essential to add to the book. They discussed traditional healing practices, before the section on modern scientific medicine, in a manner that distinguished them from an “Anglo, New Age approach.” They used, for example, Mexican folk art practices, such as religious retablos, to honor healers of the past and the foremothers of the women who worked on the translation. They addressed women’s activism throughout Latin America, such as that of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, because in their context they believed that women interested in their book would also be sympathetic to social justice movements. The American book mentioned religion only in its discussion of anti-abortion activism; the Latinas needed a fuller and more complex discussion of Catholicism. They believed its sanctity-of-life values could be transformed from a screen for enforcing motherhood and subordination onto women into the imperative of protecting the lives of children already born, of women, of communities.

Davis’s second case is the Bulgarian, where health professionals did the task in two years. Initiated after the fall of the Soviet bloc, their circumstances were both specific to Bulgaria and general to post-socialist economy and culture. Their context included rapidly worsening health, as nutrition and access to medical care plunged. Responding to a fluid situation, one that could improve but could also get worse, they conceived their book from the beginning as a work-in-progress that would be revised through reader response, as the American book turned out to be.

So the Bulgarian book, Nasheto Tyalo, Nie Samite, did not focus on over-medicalization, hardly a relevant problem. Interestingly, it did not include vignettes of Bulgarian women’s experiences. To the contrary, the translators believed that by putting the book out as a foreign text it would better arouse readers’ interest. They consciously kept taboo topics in the book — e.g., women’s masturbation, lesbianism — to provoke discussion, because those topics could not be broached then by Bulgarian feminists. Similarly they retained the U.S. chapter on abortion even though abortion was not only legal in their country but had been used as a primary form of birth control, substituting for contraception that was not widely available. They wanted readers to see a different context, in which women had to fight to retain their right to abortion. In other words, the message was not about facts or different moral or gender assumptions as much as it was about the need for democratic activism.

Many languages had not developed a way of saying what “gender” meant in the U.S.. This reflected in part the gendering of language itself — the word used in the linguistic context in Bulgaria, rod, referred to grammar and did not convey the notion of human attributes socially constructed. So they invented a new word, sociosex, as well as new expressions to refer to what we call, e.g., sexual harassment, coming out, battered women’s shelter. Now, five years later, some of these terms have already been taken up by the public.

The biggest word problem, throughout the former communist bloc, was “feminism.” That word was made pejorative from both sides: Marxist-Leninists were taught that feminism is a reactionary, “bourgeois” tendency functioning to rupture proletarian unity; while antagonists of the Communist-Party regimes hated the Soviet-type women’s organizations because they were just tools of the Party. The Bulgarians solved this problem not only by eliminating the word entirely but also by emphasizing individuality (the title uses the singular, “Our Body”). I have learned from numerous conversations how Russians and East Europeans dislike the American feminist slogan, “the personal is political.” In their recent history the extension of the political into the personal was hated, and people today cherish the right to keep their “personal” private. The Bulgarian translators wanted to encourage individual defense of rights against political power. Similarly they disliked talk of unity, universality, sameness, and emphasized instead talk of individual human variety — as they also understood the need for collective mobilization of (shhh!) feminists to become a political force.

For the Bulgarians, working in a context where gender was not a basis for progressive activism, beginning with the body — a biological reality, as opposed to gender, a cultural reality — provided “a way for Bulgarian women to begin thinking of themselves as ... subjects.” That had been true for many women in the U.S. as well, in an entirely different context.

Our Bodies Ourselves is no longer a best-seller, and the young American women I encounter have usually not heard of it. To some extent they no longer need it because, as typical post-feminists, they have received its information from mainstream youth culture, unaware of the political struggles it took to provide access to that information. HIV/AIDS also forced many (if not enough) adult authorities to get over their attempts to control teenage sexuality by depriving them of information. But health messages today typically come from a corporate commercial “healthism” in the U.S., selling goods and services as commodities, detached from any challenge to political and economic power. An oppositional health movement is no less needed today than in 1970.

But another trend is more encouraging: that the leadership of the women’s health movement - and of women’s-rights agitation generally - has passed from the developed world to the global south. Women’s health issues are embedded in movements battling neoliberal IMF “structural adjustment” requirements, pharmaceuticals’ attempts to block generic drugs, fundamentalism, privatization and “user fees” for health care and education, and, by no means least threatening, U.S. government attempts to impose bans on effective reproductive and sexual health programs. Activists in the third world must negotiate a tricky landscape in which the U.S. is often a retrograde force on women’s rights even as it is a leading source of funding for progressive programs. These feminists from Asia, Latin America and Africa, partly as a result, have avoided some of the angry rhetoric used by American feminists of 35 years ago, but they are no less committed to a similar goal: raising women’s sense of entitlement to make educated health decisions and to have the resources they need to make them. If Our Bodies Ourselves contributed even in a small way, American feminists can feel proud.

NOTE:

A shorter version of this review by Linda Gordon of Kathy Davis’ book The Making of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’: How Feminism Travels Across Borders was first published in the June 16, 2008 edition of “The Nation” magazine. Professor Gordon has kindly given us permission to print the review in its entirety.

A shorter version of this review by Linda Gordon of Kathy Davis’ book The Making of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’: How Feminism Travels Across Borders was first published in the June 16, 2008 edition of “The Nation” magazine. Professor Gordon has kindly given us permission to print the review in its entirety.

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web