Hundreds of Filipino seamen were drawn to Torres Strait from the mid-1870s by the employment opportunities and good wages offered by the pearlshell industry. ‘Pushed’ by tumultuous events in their homeland, then a Spanish colony, they worked the pearling fields close to islands which were themselves in rapid social, cultural, political and religious transition and soon to become part of the British colony of Queensland.

The Filipinos formed part of a transient workforce, accompanying the fleets across northern Australia to and from Broome and Darwin, the Aru Islands and the coasts of New Guinea. However, a number of them settled permanently in Torres Strait, the majority on Thursday Island, the commercial hub. Several families formed a Filipino outstation community on adjacent Horn Island from around 1890, from where they and their Indigenous wives, children and affinal kin worked in small cutters along coastal Cape York gathering, smoking and packing bêche-de-mer for export to the Chinese market.

Another small group of Filipinos lived with their Torres Strait Islander wives and children on Darnley Island from 1893 to about 1903, by which time most of them had left after the closure of the nearby ‘Darnley Deeps’, known as ‘the divers’ grave yard’: between 1893 and 1897 it claimed the lives of 21 Filipino divers from caisson disease (divers’ paralysis). Their bodies lie buried in graves still visible in the Darnley Island cemetery. A handful of Filipino families also lived at Yam Island near Warrior Reef, another pearling centre.

In 1912 the outer Torres Strait islands were officially designated as ‘reserves for Aboriginals’. The settlers’ children became ‘Aboriginals’, subject to the control of Queensland’s Department of Native Affairs, whereas their Filipino-descended relations from Thursday and Horn Islands were classified as ‘Australian-born Filipinos’.

Among the outer island Filipino-headed families were those of Thomas Carabello (Thomas Manilla), Juan Francisco Garcia (Johnny Francis), Joseph Kanak, Cyriaco Losbanes and Pedro Ravina from Darnley Island, the Juan Blanco and Pablo Remidio families from Murray Island, the Santiago Dorante family from Nepean Island, the Claudio (Cloudy) family from Stephens Island and the Augustino Cadaus, Isidoro Delgardo and Nicholas Sabatino families from Yam Island. Although they lived among Protestant Torres Strait Islanders, the Filipinos, who had married their wives and had their children baptised in the Catholic church on Thursday Island, kept their faith and sent their children to be educated at the Thursday Island convent.

The church had for several years wished to establish a mission in the strait on both religious and social grounds. It was originally conceived of as a home for ‘the Catholic half-castes of Torres Straits’, mostly of Filipino descent, who by the 1920s were proving an embarrassment to local Europeans. The interwar years saw one of the periodic spikes in Australian racism and there was increased hostility towards ‘miscegenation’ and a desire to remove children of mixed descent from public view. The mission would also give its residents ‘the opportunities of practising their religion’ and ‘their own homes with garden plots, [where they could] enjoy a measure of independence and detachment conducive to their general well being’.

Father John Doyle had begun gathering up suitable children, whose parents could not provide for them, soon after his arrival on Thursday Island in 1927 and set aside a part of his presbytery to accommodate the boys, the girls becoming boarders in the convent. In 1928 the church received permission to open St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Mission on Hammond Island (Keriri), immediately north of Thursday Island and a short boat ride away. Keriri belongs to the Kaurareg from south-west Torres Strait but in March 1922 the Indigenous inhabitants had been arbitrarily removed at gunpoint to Banks Island and were not allowed to return.

Fathers Doyle and McDermott, with the help of some of the older boys, began to erect a dormitory, make gardens and build a church of swamp mangrove and galvanised iron. Father Doyle officially opened the mission with a Mass on Ascension Thursday, 10 May 1929. In the four years between 1929 and 1933 the Queensland government provided it with yearly grants totalling £250.

Soon after the formal establishment of the mission Father Doyle set about increasing its population, urging Catholic families living in the outer islands to exchange departmental for church control. He had already gained assurances from ‘a few old Manila men’ that they would come and teach the boys to work the land, grow vegetable gardens and look after livestock. Joseph Kanak from Guam, his wife, Raphaela, and their seven children were the first family to apply to settle on the mission. Though living on Darnley Island, ‘consideration of their present and future welfare prompted him to be the first applicant for settlement on the new mission. Father Doyle gladly granted Joe’s request, and the old man [then in his 60s] set about transferring his home from Darnley Island to Hammond Island — a distance of 120 miles.’

They were joined by Nicholas Sabatino from Iloilo, his wife, Johanna, and their five children, then living on Yam Island, and the family of Harry Sebasio, born on Raratonga but raised on Rotuma, and his wife, Dalassa from Darnley Island, whose first ten children were born on Darnley. Some of Samar-born Santiago Dorante’s children followed, although Dorante himself remained at Nepean Island and other children went to neighbouring Stephens Island. Thus, three of the first four families were headed by Filipinos whose wives were locally-born daughters of Filipino fathers: Raphaela Francis Kanak, Johanna Lohado Sabatino and Wasada Napoleon Dorante.

By 1931 several families had arrived, with more families and boys waiting to come as soon as they could be accommodated. A further four children were born to the Kanaks on the mission; a further two to the Sabatinos; and the Sebasios’ eleventh child, Jerry, was born there in 1933. Others who joined the mission in its early days were the elderly widowers, Pablo Remidio from Ilocos and Isidoro Delgardo from Algal. Both were suffering from recurring leg pain as a result of divers’ paralysis and unable to work in the marine industries; they were dependent on the mission and granted government indigence allowances in the late 1920s. Delgardo died and was buried at the mission in 1940; Remidio died on Thursday Island in 1941. Augustino Cadaus from Ilocos remained on Yam with his two married daughters and Islander grandchildren until his death in 1952. Cadaus was the last Filipino seaman to die in Torres Strait.

St Joseph’s Mission celebrated its first birth when Monica Sabatino arrived on 5 May 1930 and its first wedding when Antonio Dorante married Felicia Jack from Darnley Island on 9 October 1930. The first death may have been Antonio’s brother, Napoleon, on 1 June 1933. Other Catholic families with a Filipino connection who lived at the pre-war mission include Annie Blanco, widow of Juan Blanco, and her third husband, Bob Quetta; Annie’s son and daughter- in-law, Silverio and Josephine Blanco; Annie Randolph Lopez, widow of Lopez de la Cruz, with her youngest children, Eva, Thomas and May, and her married daughters Josephine Salam Blanco and Isabella (Dolly)Lopez Corrie; the Canendo brothers, Alfonso and Marcellino, with their wives Petronilla Sabatino Canendo and Nancy Sebasio Canendo; and wheelchair-bound Stephen Gallardo, son of Louis Castro Gallardo, together with his second wife Louisa Savage Mallie.

Father McDermott set up a school, which was staffed by brothers of the French order, Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC), until the MSC sisters were installed on 26 February 1936. By 1938 it had 35 pupils and the mission’s population had grown to 122. In early 1942 the women and children were compulsorily evacuated to Cooyar, near Toowoomba. Francis Dorante, who was awarded a Royal Humane Society medal for bravery after rescuing two women from drowning, was the last civilian to leave the island when the Japanese made their first air raid on Horn Island in early March 1942. Cooyar closed in November 1944 but by then most of the mission residents had gone elsewhere.

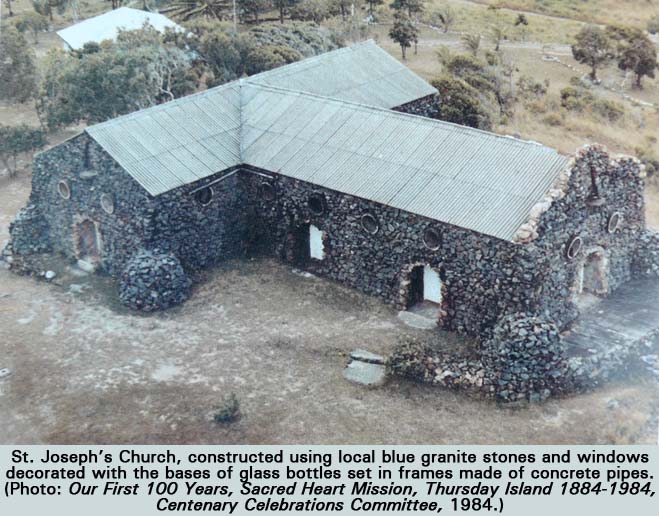

Only a minority of the original inhabitants returned to Hammond Island after the war, instead remaining in mainland cities and towns in north Queensland. The Sabatino and Dorante families were the first to resettle in 1947 and about six families were living there by the end of 1949. In 1952 the residents began building the mission’s distinctive blue granite church, which was opened on 9 May 1954. A visitor described it as a ‘Romanesque-style, grey stone building, like the hallowed county church in England’. It is an impressive regional landmark but, like the modern Torres Strait Islander community it serves, it has little apparent connection with the early mission’s predominantly Filipino character, which survives only in photographs and the memories of its few remaining pre-war residents.

Hundreds of Filipino seamen were drawn to Torres Strait from the mid-1870s by the employment opportunities and good wages offered by the pearlshell industry. ‘Pushed’ by tumultuous events in their homeland, then a Spanish colony, they worked the pearling fields close to islands which were themselves in rapid social, cultural, political and religious transition and soon to become part of the British colony of Queensland.

The Filipinos formed part of a transient workforce, accompanying the fleets across northern Australia to and from Broome and Darwin, the Aru Islands and the coasts of New Guinea. However, a number of them settled permanently in Torres Strait, the majority on Thursday Island, the commercial hub. Several families formed a Filipino outstation community on adjacent Horn Island from around 1890, from where they and their Indigenous wives, children and affinal kin worked in small cutters along coastal Cape York gathering, smoking and packing bêche-de-mer for export to the Chinese market.

Another small group of Filipinos lived with their Torres Strait Islander wives and children on Darnley Island from 1893 to about 1903, by which time most of them had left after the closure of the nearby ‘Darnley Deeps’, known as ‘the divers’ grave yard’: between 1893 and 1897 it claimed the lives of 21 Filipino divers from caisson disease (divers’ paralysis). Their bodies lie buried in graves still visible in the Darnley Island cemetery. A handful of Filipino families also lived at Yam Island near Warrior Reef, another pearling centre.

In 1912 the outer Torres Strait islands were officially designated as ‘reserves for Aboriginals’. The settlers’ children became ‘Aboriginals’, subject to the control of Queensland’s Department of Native Affairs, whereas their Filipino-descended relations from Thursday and Horn Islands were classified as ‘Australian-born Filipinos’.

Among the outer island Filipino-headed families were those of Thomas Carabello (Thomas Manilla), Juan Francisco Garcia (Johnny Francis), Joseph Kanak, Cyriaco Losbanes and Pedro Ravina from Darnley Island, the Juan Blanco and Pablo Remidio families from Murray Island, the Santiago Dorante family from Nepean Island, the Claudio (Cloudy) family from Stephens Island and the Augustino Cadaus, Isidoro Delgardo and Nicholas Sabatino families from Yam Island. Although they lived among Protestant Torres Strait Islanders, the Filipinos, who had married their wives and had their children baptised in the Catholic church on Thursday Island, kept their faith and sent their children to be educated at the Thursday Island convent.

The church had for several years wished to establish a mission in the strait on both religious and social grounds. It was originally conceived of as a home for ‘the Catholic half-castes of Torres Straits’, mostly of Filipino descent, who by the 1920s were proving an embarrassment to local Europeans. The interwar years saw one of the periodic spikes in Australian racism and there was increased hostility towards ‘miscegenation’ and a desire to remove children of mixed descent from public view. The mission would also give its residents ‘the opportunities of practising their religion’ and ‘their own homes with garden plots, [where they could] enjoy a measure of independence and detachment conducive to their general well being’.

Father John Doyle had begun gathering up suitable children, whose parents could not provide for them, soon after his arrival on Thursday Island in 1927 and set aside a part of his presbytery to accommodate the boys, the girls becoming boarders in the convent. In 1928 the church received permission to open St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Mission on Hammond Island (Keriri), immediately north of Thursday Island and a short boat ride away. Keriri belongs to the Kaurareg from south-west Torres Strait but in March 1922 the Indigenous inhabitants had been arbitrarily removed at gunpoint to Banks Island and were not allowed to return.

Fathers Doyle and McDermott, with the help of some of the older boys, began to erect a dormitory, make gardens and build a church of swamp mangrove and galvanised iron. Father Doyle officially opened the mission with a Mass on Ascension Thursday, 10 May 1929. In the four years between 1929 and 1933 the Queensland government provided it with yearly grants totalling £250.

Soon after the formal establishment of the mission Father Doyle set about increasing its population, urging Catholic families living in the outer islands to exchange departmental for church control. He had already gained assurances from ‘a few old Manila men’ that they would come and teach the boys to work the land, grow vegetable gardens and look after livestock. Joseph Kanak from Guam, his wife, Raphaela, and their seven children were the first family to apply to settle on the mission. Though living on Darnley Island, ‘consideration of their present and future welfare prompted him to be the first applicant for settlement on the new mission. Father Doyle gladly granted Joe’s request, and the old man [then in his 60s] set about transferring his home from Darnley Island to Hammond Island — a distance of 120 miles.’

They were joined by Nicholas Sabatino from Iloilo, his wife, Johanna, and their five children, then living on Yam Island, and the family of Harry Sebasio, born on Raratonga but raised on Rotuma, and his wife, Dalassa from Darnley Island, whose first ten children were born on Darnley. Some of Samar-born Santiago Dorante’s children followed, although Dorante himself remained at Nepean Island and other children went to neighbouring Stephens Island. Thus, three of the first four families were headed by Filipinos whose wives were locally-born daughters of Filipino fathers: Raphaela Francis Kanak, Johanna Lohado Sabatino and Wasada Napoleon Dorante.

By 1931 several families had arrived, with more families and boys waiting to come as soon as they could be accommodated. A further four children were born to the Kanaks on the mission; a further two to the Sabatinos; and the Sebasios’ eleventh child, Jerry, was born there in 1933. Others who joined the mission in its early days were the elderly widowers, Pablo Remidio from Ilocos and Isidoro Delgardo from Algal. Both were suffering from recurring leg pain as a result of divers’ paralysis and unable to work in the marine industries; they were dependent on the mission and granted government indigence allowances in the late 1920s. Delgardo died and was buried at the mission in 1940; Remidio died on Thursday Island in 1941. Augustino Cadaus from Ilocos remained on Yam with his two married daughters and Islander grandchildren until his death in 1952. Cadaus was the last Filipino seaman to die in Torres Strait.

St Joseph’s Mission celebrated its first birth when Monica Sabatino arrived on 5 May 1930 and its first wedding when Antonio Dorante married Felicia Jack from Darnley Island on 9 October 1930. The first death may have been Antonio’s brother, Napoleon, on 1 June 1933. Other Catholic families with a Filipino connection who lived at the pre-war mission include Annie Blanco, widow of Juan Blanco, and her third husband, Bob Quetta; Annie’s son and daughter- in-law, Silverio and Josephine Blanco; Annie Randolph Lopez, widow of Lopez de la Cruz, with her youngest children, Eva, Thomas and May, and her married daughters Josephine Salam Blanco and Isabella (Dolly)Lopez Corrie; the Canendo brothers, Alfonso and Marcellino, with their wives Petronilla Sabatino Canendo and Nancy Sebasio Canendo; and wheelchair-bound Stephen Gallardo, son of Louis Castro Gallardo, together with his second wife Louisa Savage Mallie.

Father McDermott set up a school, which was staffed by brothers of the French order, Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC), until the MSC sisters were installed on 26 February 1936. By 1938 it had 35 pupils and the mission’s population had grown to 122. In early 1942 the women and children were compulsorily evacuated to Cooyar, near Toowoomba. Francis Dorante, who was awarded a Royal Humane Society medal for bravery after rescuing two women from drowning, was the last civilian to leave the island when the Japanese made their first air raid on Horn Island in early March 1942. Cooyar closed in November 1944 but by then most of the mission residents had gone elsewhere.

Only a minority of the original inhabitants returned to Hammond Island after the war, instead remaining in mainland cities and towns in north Queensland. The Sabatino and Dorante families were the first to resettle in 1947 and about six families were living there by the end of 1949. In 1952 the residents began building the mission’s distinctive blue granite church, which was opened on 9 May 1954. A visitor described it as a ‘Romanesque-style, grey stone building, like the hallowed county church in England’. It is an impressive regional landmark but, like the modern Torres Strait Islander community it serves, it has little apparent connection with the early mission’s predominantly Filipino character, which survives only in photographs and the memories of its few remaining pre-war residents.

Related Article:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web