It was inevitable for me to stumble upon Paschal Daantos Berry’s The Folding Wife. As a postgraduate student researching the Filipino-Australian migrant community, I have had a few encounters with the play although not as a performance; first as an object of critical study in publications and second as a written text in an anthology called Salu-salo: In Conversation with Filipinos.[*]

On tour to Mackay, Townsville, Darwin, Cairns, Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne in April and May this year, the play directed by Deborah Pollard is a not-to-be-missed cultural text for any student of Australia’s social history of migration, in particular, that which involves the Filipina women who came as ‘brides’. More so, The Folding Wife is a definitive example of a presentation of how the Filipino attempts to rewrite and reconstruct their Australian identity through self-representation; crucial, too, for plays like this one are not made for one’s own people, but for others.

In a ‘biographical fiction’ formatted into a monologue for theatre, The Folding Wife is a narrative composed of a multi-layered polyphony of voices. We meet Clara (the Hispanic-rooted but America-loving grandmother), Dolores (the ‘mail-order bride’ migrant) and Grace (the Filipina-Australian granddaughter). Their names are an obvious giveaway of the characterisations that the playwright wanted them to embody: Clara as a source of clarity and wisdom of the past, Dolores as the woman whose sorrow manoeuvred her escape, and Grace as the young woman who has learned to embrace the challenges and the benefits of her migration evident in her Anglophone name. Valerie Berry, in an amusingly Pinoy-accented English, capably played each role; although there were times when one wondered if three actors, instead of one, could have rendered a more nuanced performance.

Without doubt, at the centre of the text/performance is the ‘woman question’; the title, the material, the narrative framing, the props, the images projected on a screen, and yes, the ‘Filipina’ as a political subject feminised and sexualised by her migration all pointed to this reading. The Folding Wife, conceived in 2002 by the collaborative work between the playwright Paschal Daantos Berry and his sister Valerie Berry, is a looking back at the Filipina ‘mail-order bride’: the stigmatised pathological outsider in the Australian psyche as imagined by its media. It is a tidy attempt at representing the Self; an effort to wash off a soiled laundry that has come to wrap all Filipino women in the spectrum — from middle-class professionals to former sex workers — as Third World women singular in their quest to cross the boundaries of race and class.

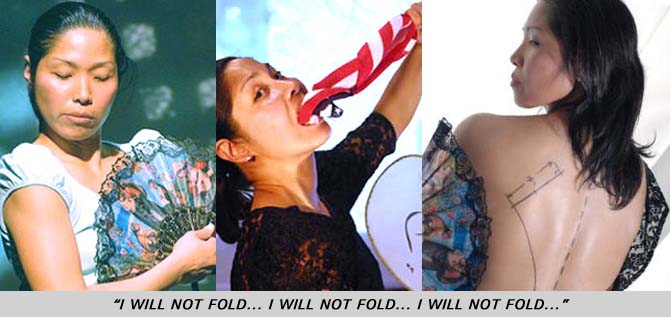

Anchoring the narrative on the colonial past and postcolonial republican fascism of the Marcos era, the play sought to plumb the depths of Filipino culture and social history to explain why its women undermined the sacrality of the bed and matrimony for the sake of an Australian visa; an unforgivable breach of ‘femininity’ to a white supremacist and patriarchal culture. The political approach to the theme is evident in the very opening of The Folding Wife where Valerie Berry is a half-naked mannequin being fitted with all sorts of clothes, props and symbols of the Philippine postcolonial condition. The Filipina as an embodied subject prostituted — both in its physical and political senses — is shown through the imagery of the gaudy stripper wrapped in a star-spangled banner or a uniformed maid robotically wagging a feather duster. Two pictures that are one and the same in the world where migrant labour is necessitated by transnational capital and sex is ‘rest and recreation’ for roving superpowers. The irony and humour of the opening scene — which the entire audience missed except for the few Filipinos present — are underlined by the musical scoring; lines such as ‘bakit kaya may ligaya’t lumbay?’ (why is there happiness and sadness?), ‘ang dalagang Filipina malinis ang puso’ (the Filipina woman has a pure heart) and ‘Lord, give me a lover’ add to the pain against which every Filipino woman has to struggle.

The Folding Wife, however, has a rather interesting plot that is easier to deal with than real life; a quaint familial history more palatable than the more common story of a ‘mail-order bride’. Clara clings to a lineage of peasant gentry where her family could afford quality furniture from the Villaceran’s; a dignified existence within the confines of semi-feudal provincial life. Her notion of a venerable status is sadly anchored on racial biases that define Philippine society but ignored nonetheless. When Clara narrated how the Chinese store owner survived the onslaught of the Japanese occupation because the ‘Chinese stick to themselves’ (a perception of economic and racial clannishness) and that ‘because they have the same eyes’ (biological racialism that does not take into account Sino-Japanese relations and Chinese resistance in the war), she unpacks a mine of social tension within Philippine society; a knee-jerk comment not only classist but also racist. Moreover, the circumstances of Dolores’s ‘disgrace’ — being querida then impregnated by a married man — which brought forth Grace were enveloped within the discourse of ‘true love’; an easy textual manoeuvring that is later juxtaposed with the Australian. Dolores needed salvation — economic and otherwise — which only a new life, a new man in a new found land could give. Contextualised within the fascistic magic realism of Marcos and Imelda’s regime, Dolores had to escape.

However, did The Folding Wife explain what it aimed to explain to its city-bred, middle-class Australian audience? While I recognise that it may be too difficult to hinge the ‘woman question’ — of which the ‘mail-order bride’ discourse is very much a part — in a family-based play to the feminisation of labour in the Third World that initiated the exodus of women, not to insert it in a ‘revisionist’ material would be on the other hand a disservice. It must be recognised that for any ‘ordinary’ Australian, a Filipina is, nothing more and nothing less than, an impoverished sex-enslaved bride; she cannot exist outside it. Now, to belabour the fact that some Filipinas have a decent family history, educated, not really poor, etcetera, is to miss the point why such a sexist discourse exists in the first place. I fear that The Folding Wife did not erase what is politically and ethically erasable; instead, the audience would leave the theatre thinking the same thoughts as when they entered. I definitely hope I am wrong.

The performance is laudable in many aspects. Backed by its talented crew and creative props that remind me of college plays back at the University of the Philippines, this production is mobile and inexpensive to stage. It is also praiseworthy for its attempt to resurrect a dormant social issue hiding behind the formation of a new ensemble of migrants based on their professional skills. While never dormant, for history is almost always the bedrock of common-sense perceptions, The Folding Wife deserves a credit for its effort to penetrate the cosmopolitan Australian audience with this topic. In its Carriage Works venue, a stone’s throw away from the University of Sydney in gentrified Redfern, one can feel that these are no ‘ordinary’ Australians, at least not the ‘bogans’ (a word I picked up here and use in the context of its Australian origin, class-biased and all) binge-drinking at a bar. One would expect this audience would know what the ‘Filipina question’ is in relation to them in a politicized way. However, on my way out of the theatre, I overheard a conversation amongst three Australians: “So, what exactly is the play about?” The other replied: “I honestly don’t know. I really don’t.” While this reception of the play could be the exception rather than the norm, it is still symptomatic of what the performance lacked: a clarification of a sorrowful episode of sexualised Filipina migration in Australia that until now has not given her a graceful exit.

Somewhat unsure of what I thought about The Folding Wife, I asked my Latin American friend if the play was clear enough to be understood. (Her knowledge of Philippine-Latin American historical links and gringo political interventions and its effect on its people is quite good.) “No,” she said, “it was not clear.” Finally, I remembered the entire audience reaction: quiet when I and the other Filipina sitting across muffled what was threatening to become a loud guffaw in hearing familiar cultural references; the short snigger upon hearing the line, “so that should shut those convicts up”; and the lukewarm applause at the end. That said, am I proud to have watched The Folding Wife: a story of my people, so to speak? I suppose, yes.

Endnote:

Endnote: Anino Shadowplay Collective is a Manila-based group of multimedia artists dedicated to popularising the art of shadow play. Visual artists Datu Arellano and Teta Tulay performed in the 2010 tour. From 2005, the Anino Collective collaborated with Paschal Berry to bring colour, light, imagery and sensuous visual texture onto the stage.

About the Reviewer:

Shirlita Espinosa is a full-time PhD candidate at the University of Sydney. She is working on the migrant print material culture of Filipinos in Australia. Her studies are made possible by Ford International Fellowship Program.

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web