The easy movement of labour across international borders is a feature of globalisation and the resulting complex connectivity. Ten years hence the Australian government granted a total of 86,970 temporary working visas (43,580 to primary applicants and 43,390 for their dependants). The top four source countries for these applications are: United Kingdom (19,270), Philippines (9,260), India (8,530), and South Africa (5,030).[2] While there has been a downward trend in applications since 2008 due to the global recession, what these figures indicate is that ‘labour’ is an international commodity that can readily be transacted across borders.

As of June 2008, temporary 457 visa holders and their dependants were around 130,000 people; working holiday makers around 90,000; and international students around 320,000. All of these half a million temporary migrants – comprising almost 5 per cent of the total labour force – have work rights.[3]

One advantage of this cross-cultural experience is we can compare working conditions in different parts of the world from the workers’ actual experience. This helps us monitor differences in the application of ‘workplace fairness and equity’ practices. It also gives us a picture of the human face of the globalised labour flow.

Take the experience of Eduardo Tomas, a Filipino from Kuwait, who was recruited to Broome, Western Australia.[4] When Dee Hunt and I went to Broome last year, we had a chat with a number of Filipinos like him, who live and work there.

Eduardo said:

“If you compare my work experience here with the Philippines and Kuwait, there are huge differences. It’s natural that if you are in the Philippines, your work mates are Filipinos; if you are in an Arabic country, your workmates are Arabs; in Australia, your workmates are English speaking.

“Culture played a significant role whichever country we worked in; so was the workplace environment. In the Philippines, one worked incessantly, but it was never enough. When we got to the Middle East, the benefits were average. We could say that my work of four years would be equivalent to a year here.

“I can’t say yet what my preference is considering I’ve only been here a month. Perhaps in 3-4 years time, I’d be able to say. On the question of whether I would like to stay [permanently] in Australia, which Filipino would not say, ‘there is no place like home’? If we say in the 1970s in Saudi Arabia that Saudi is the green pasture, you could also say that Australia and New Zealand are green pastures.”

Eduardo also compared his experience of workplace practices between Kuwait and Australia in his position as Manager of a retail food outlet:

“When I was in Kuwait, I worked as the Store Manager. It was mainly office work. I gave the orders, trained people what they had to do. Different here where I could find myself holding rags, cleaning the toilets, which was not needed. This was not what I was led to believe from my boss or from what I had read on paper. I think that this [blurring of responsibilities] could have happened because at the start, leadership left something to be desired [referring to workplace culture that preceded his appointment]. If I had started implementing sound leadership from the start, then the running of the enterprise would be sound from the beginning. I’m starting gradually to implement change. I know that they are starting to feel this. Maybe in three months time, I could change things.

“I was used to employees aged from 20 up. Only here did I experience having to do with employees who are aged 12, 13 or 14. When I look for these children, they sometimes go missing. If I wanted something done, they’d say ‘ok’, but they don’t do it. They just play. So maybe we need to start with an appropriate approach.

“In the Middle East, minors are not allowed to work. In Australia, children are allowed to work sometimes. Here we encourage children to work so they get work experience and they are also ‘free’ to work. All that is needed is to implement the right policy and approach. Not an approach that is seen as ‘discipline’, rather as a ‘directive’ of what job needs to be done.

“My boss says things are like this because we are in Broome. I can’t comprehend this argument. How is it that because we are in Broome, we can’t straighten things out? My first step is to do something with the children – such as ways to get things working better – not harsh, not too friendly, not too playful. There must be a way. That is an ‘assignment’ I have given myself for around three months from now. This is not in consultation with my boss, this is my own commitment to myself.

“At the moment, we are confronted with different behaviour. Some children are straight, they do what they are told to do. Some are indifferent. You tell them everything, give them everything – yet there is no result. We just can’t let them go. They resign on their own accord sometimes because they still haven’t learnt the job. If school is on, they are allowed to work from 3-8pm. If we employ backpackers, these ones move around Australia – so after 6 months, ‘goodbye’. “Really our training is only good for 3 months. Anyone trained for 3 months should be excellent. One week training is okay. If I train them for 3 months, I feel my investment is wasted if, after this, they leave us.”

Many overseas workers like Eduardo are willing to sacrifice leaving their home country to maintain a decent living standard for their family. The economic pull is obviously a strong motivation. But there are challenging pitfalls in making such a move. Temporary overseas workers can stay in Australia only for as long as they can hold onto their jobs, so they are extremely vulnerable and easy prey for exploitation.

One problem is their employers are meant to have given specific undertakings in relation to their working conditions such as: payment of certain costs, including ensuring the cost of return travel for visa holders; meeting public health costs (other than those covered by health insurance or reciprocal healthcare arrangements) and the cost of locating and removing the employee if they become unlawful; complying with immigration laws; cooperation with the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (including notification of change in circumstance over the employment arrangements); complying with the terms of nomination of the position and with workplace relations laws.

But arrangements and processes regarding compliance with these undertakings are not well defined and sanctions for infringement are rarely enforced, assuming that workers, employers and migration agents understand what these undertakings mean in practice.[5]

Eduardo spoke of his experience:

“In terms of the cost of living, our accommodation expenses are huge, nearly half my salary goes to housing. My wife also works. My boss is Australian – I don’t know how he surveys policy when it comes to a 457 visa holder. Apart from tax and superannuation, there ought not to be any deduction from my pay. There ought not to be any deduction for accommodation. [My wife] is only allowed to work for 10 hours a week, and 10 hours yields about $200, but in reality, we pay $480 per week. …Our only real challenge when we arrived here was food because we didn’t know where to buy recipes for food. But we adapted quickly. Whatever is around, we were able to convert to Filipino cuisine.”

Another Filipino 457 visa holder we interviewed, Ric Romero, recounted the trouble he had with his former employer. [6] He lasted twenty months working for this employer until he independently secured another position so that he could remain working in Australia.

Ric narrated his story:

“Before I left [the company], I asked my boss if they can organise my transport going to Kununurra because that was the home base. And that afternoon, I went to the Greyhound Bus and then organised for my bus fares. I paid that with my own money but my boss said that I can [get] reimbursed for that when I reached Kununurra. Then when I went to Kununurra I wasn’t able to [get it reimbursed]. I wasn’t able to get my last three pay slips, and then they deducted $750 for the visa of my family from my pay.

“I already had a feeling that they had changed my salary rate from the standard 457 salary to a $25 per hour flat rate, so if you only work for an hour a day, you only get $25. They changed my working hours. So I decided that I have to stop this. I have to leave and look for a much better company. Also I asked the wife of my boss if they could send my last three pay slips and other documents that I need, but after a month there was nothing in the post or in the mail box so I e-mailed them asking where are my last three pay slips, where are the details of my superannuation and the reimbursement for my bus fare and the other documents that I needed, also the separation certificate. They said it was already posted and here comes [the] letter saying that I owed them money for the immigration fees, I owe them money for the rent and food, power and office things.”

“How much did they say you owed?” we asked.

“About $3,000. The thing is, they only informed me after four months [when] I was already out of the company. I already resigned. I gave them four weeks notice before I left the company but they didn’t forward any breakdown or notice that I still owe them money.

“I asked the Migration Agent who [processed] my sponsorship how many weeks should I give notice if I … resign so they told me, “two weeks”. I already gave my resignation and then I gave them two weeks, and after that they asked me if I could stay [longer], and I told them that I could only stay another two weeks, so that is four weeks all in all. So in that period, they should have informed me that I owe them money, that they already computed all things, especially with the holiday pay.”

Clearly temporary overseas workers, if not treated appropriately and not provided with full information about their rights and obligations, are likely to find themselves in a sticky situation.

To improve transparency, the final report of the Visa Subclass 457 Integrity Review, conducted by Ms Barbara Deegan, recommended that the names of sponsors with 20 or more Subclass 457 visa holders be published on the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) website.[7] The idea behind this is to allow 457 visa holders dissatisfied with their current situation to check other potential employers thus enhancing the possibility of their mobility. Some sponsors are unhappy with this proposal fearing that certain union organisations in their campaign against temporary overseas workers would use this information to target employers.

Deegan’s review noted that some sponsors with large initial cost outlay in obtaining overseas workers hold an attitude of ‘ownership’ over the visa holders. Others seem to expect visa holders to contribute to the upfront costs already incurred. To immediately recoup their costs, some sponsors deducted their outlay from the workers’ wages. Cultural adaptation is hard enough for these workers without having to suffer economic woes and insecurity at the beginning of their settlement.

In the last few years, a huge shift has occurred in Australia’s skilled migration programs from permanent to temporary residency. Government planned migration has shifted to a greater dependence on ‘employers’ sponsorship’, international students, backpackers and holiday makers being given conditional rights to work. In this sense, the whole focus is on the immediate supply of labour requirements, obviously at the expense of long term planning for training of existing Australian citizens and permanent residents. With international students, one could see the ‘savings’ the Australian Government anticipates from long term training via these originally fee-paying students whose early education was financed by the source countries, and who, conditions permitting, could convert their visas later to permanent residency status.

Furthermore, the profile of nominated occupations seems to fall across the board of a variety of job categories from ‘professional’ to ‘trades’. Noteworthy is the labour shortage reflected in the top four 457 ‘professional class’ recruits: computing professionals, registered nurses, business and information professionals, and general medical practitioners.[8] One hopes that structural cracks that may appear later with this migration policy shift, such as inconsistency in delivery standards in some occupational categories, will not simply be papered over by our politicians and policy planners.

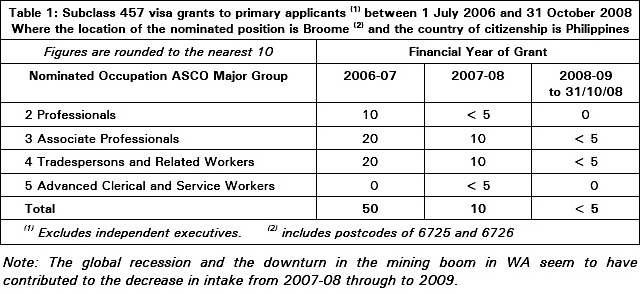

While the WA Government in its response to the Deegan review had rationalised the increase of skilled migrants to help alleviate labour shortages,[9] the downward trend in ‘arrival statistics’ for 457 visa holders in Broome from 50 in 2006-07 to 10 in 2007-08 to less than 5 in 2008‑09 seems to reflect a level of uncertainty in the current economic climate. An example in Table 1 below is the nominated occupation profile of Filipino 457 visa holders from 2006 to 2009, who went to Broome, W.A.:[10]

In the March 2009 report on trends in the 457 visa program, the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) notes that the decline in demand for 457 visas “is reflecting changes in the global and local economic environment. Primary visa applications in March 2009 were 33% lower than September 2008”.[11]

But the Commonwealth government has another strategy to hang on to the ‘temporary’ workers who their employers say they still need. These workers, on the recommendation of their sponsors, can apply for permanent residency. This ‘flow’ of subclass 457 visa holders to permanent residence is confirmed by the DIAC report: “The number of permanent visa grants in March 2009 to primary applicants where the person last held a Subclass 457 visa was 10% greater than those in February 2009 and 89% greater than March 2008.” [12]

Globalisation has brought challenges for Australia in the twenty-first century, including the old and familiar jingoist anxiety over erosion of wages and conditions by ‘cheap’ migrant labour. If trade union leaders target employers who are undermining hard-won working conditions, they put temporary overseas workers’ ability to stay in the country in jeopardy. And if they don’t, their own members’ working conditions are under threat and exploitative employers will get away with their unfair practices with impunity.

In the face of global recession, union leaders are more likely to call for migrant workers to be dismissed before locals. Globalisation amounts to ‘complex connectivity’ indeed as the intrinsic contradictions of the market economy, combined with the nationalist/protectionist predispositions of locals, challenge the reality of lack of parity in working conditions both nationally and internationally. In the current climate of international competitiveness over the commodity of flexible transnational labour, one wonders just how well the solidarity amongst workers of the world will fare?

[1] John Tomlinson, Globalization and Culture, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999, pp. 1-2.

[2] Subclass 457 Business (Long Stay) - State/Territory Summary Report 2008-09, Report Id: BR0008, Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship. http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/pdf/457-stats-state-territory-feb09.pdf; The Subclass 457 visa program was introduced to enable Australia to remain internationally competitive in facilitating the movement of labour to support Australia’s skills needs. It was initiated by the Keating government and introduced in 1996 by the Coalition. It allows employers to sponsor skilled workers from overseas for between three months and four years.

[3] Mares, Peter. ‘The permanent shift to temporary migration’, Inside Story, 16 June 2009, http://inside.org.au/the-permanent-shift-to-temporary-migration/

[4] Interview with the author, 5 September 2008. Eduardo Tomas is not his real name.

[5] Deegan, Barbara. Visa Subclass 457 Integrity Review, October 2008, Australia, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, p. 70, http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/_pdf /457-integrity-review.pdf; A “significant” proportion of the $19.6 million in the 2008-09 Federal Government’s Budget earmarked for enhanced arrangements for temporary working visas, will go to support the introduction of legislation that better defines employers’ obligations and improve investigative powers to increase protection of workers’ rights. (The Review was conducted by Ms Barbara Deegan, an industrial relations expert appointed by the Deputy Prime Minister and the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship.)

[6] Interview with the author, 8 September 2008. Ric Romero is not his real name.

[7] Deegan, op. cit. p. 14.

[8] Subclass 457 Business (Long Stay) - State/Territory Summary Report 2008-09, op. cit.

[9] See Visa Subclass 457 Integrity Review: English Language Requirement/Occupational Health and Safety, Government of Western Australia Response to Deegan Issues Paper #2, Released August 2008, and Visa Subclass 457 Integrity Review: Integrity/Exploitation, Government of Western Australia Response to Deegan Issues Paper #3, Released September 2008, Office of Multicultural Interests, Department for Communities, http://www.omi.wa.gov.au/omi_submissions.asp

[10] Supplied to the author on 16 December 2008 by the Statistics Management Unit, Labour Market Branch, Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

[11] Trends in the Subclass 457 Business (Long Stay) Visa Program to March 2009, Report ID: BR0060, p. 1, http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/pdf/457-march-trends.pdf

[12] Trends in the Subclass 457 Business (Long Stay) Visa Program to March 2009, op. cit. p.2

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web