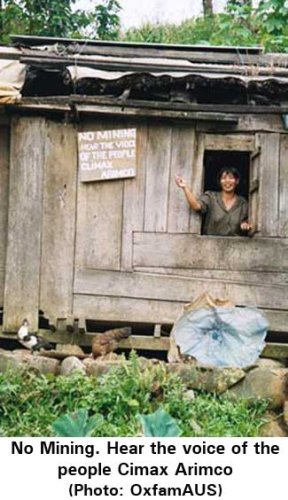

Juanita Cut-ing is just one woman but her story, reported in The Age recently, says much about the way mining companies in search of enormous profits have exploited people in the developing world. Cut-ing and her family live in a stilt home in the remote village of Didipio in the north of the Philippines, but their land is destined to make way for a dam to store waste from an open–pit gold and copper mine operated by Melbourne-based OceanaGold. The company says it will provide jobs and improved infrastructure, but its plans will destroy Cut-ing’s dream of passing her house and land to her children.

The Australian mining industry is one of the most active in exploiting resources in developing countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Pacific region. The industry and, indirectly, the Australian people are reaping the rewards of this activity. As shareholders, we receive dividends and a booming mining industry contributes revenue to our economy.

So how is it that we, as beneficiaries of these activities, are yet to compel our mining companies to respect the rights of the communities in which they operate when abroad? There are, unfortunately, too many examples of Australian mining companies being associated with environmental damage, complicity in human rights abuse and allegations of corruption.

A pattern emerges: communities in Papua New Guinea continue to live with the devastating practice of disposing of mine waste into valuable waterways still used at Ok Tedi and by Emperor Mines at Tolukuma; Congolese community members are considering legal action against Anvil after deadly military suppression; and an independent investigation by The Age recently confirmed that “irregular offers” were made by Climax Mining (now OceanaGold) when it was seeking local government approvals in the Philippines. In each case, the activities of Australian companies have been brought into question.

There have been enough complaints from affected communities that have gone unheeded by both Australian mining companies and the governments of the countries in which they operate that Oxfam Australia established a mining ombudsman. Almost invariably, the worst impacts on communities are experienced in countries where law and order is lax, where regulations are inadequate, and where capacity and political will to enforce the law don’t coincide.

Through the mining ombudsman, we have documented evidence that the victims of poor corporate practices are often those who can least afford it: the local communities. They are the very people whom the economic prosperity of development should be helping most.

The ombudsman has made clear the benefits of ensuring that community complaints are heard by companies and that a resolution is reached. The Mining Ombudsman has also assisted companies to understand the concerns of communities and work collaboratively in search of solutions. In the case of the former BHP Billiton Tintaya mine in Peru, there was a turnaround in community relations when a dialogue process was entered.

Yet a not-for-profit development agency does not have the resources to respond to the increasing number of community requests received. Nor does Oxfam believe the mining ombudsman should ultimately be a role assumed by a non-government organisation. Rather, Australian industry and government should establish a complaints procedure based on the mining ombudsman model.

Internationally, those seeking an innovative model to assist in the complex relationship between mining and human rights are learning from this model. In Canada, for example, a process that included mining companies and government recommended the creation of a Canadian ombudsman for the mining, oil and gas sectors in their operations abroad. Oxfam Australia is also sharing its experiences with the United Nations Secretary-General’s special representative on business and human rights.

There is an opportunity for the Federal Government to work with mining industry leaders in examining how to lift the standards and practice of the sector when it operates overseas. A complaints mechanism for overseas communities harmed by the activities of some Australian-owned mine operators would be an initiative to help generate greater accountability.

There is little doubt that the mining industry can bring about economic development and poverty alleviation. There is also no doubt, however, that a failure to respect human rights and the environment is counter-productive to development. When corporate activities and human rights abuses coincide, there are no winners.

Australia is reaping the rewards of an extended mining boom so both government and industry can well afford to devote some of the profits to ensuring communities’ grievances are heard and resolved. We should not enjoy the riches of this mining boom without protecting the lives and livelihoods of those whose resources are being extracted for our benefit.

See Also:

Further Reading:

27 March 2008

Oxfam Australia is calling for an independent inquiry to determine whether the opposition of residents in a remote community in the Philippines is being appropriately responded to by Melbourne based mine operator OceanaGold, which plans to develop a gold and copper mine in the village of Didipio. The move follows reports that a security guard from the mine shot and wounded a villager.

According to The Philippine Daily Inquirer, the incident took place at around 11am, on 22 March when a demolition team from OceanaGold commenced tearing down the home of a local resident, reportedly asleep in the house at the time. According to the acting provincial police director, a group of local men rushed to the aid of the sleeping man and, in the process, one of the local men, Emilio Pumihic, was shot in the arm by a guard of OceanaGold.

‘This is a very serious incident,’ said Oxfam Australia’s Mining Ombudsman, Shanta Martin. ‘An independent inquiry is needed to inquire into grievances that have long been raised by opponents to the mine operation and the extent to which OceanaGold’s actions are consistent with the human rights of those that have lived in Didipio for generations,’ Ms Martin said.

The incident follows a report published last year by Oxfam Australia, following five years of investigation, which found that many villagers in Didipio complained of harassment and intimidation by agents of the Melbourne-based mine operator. Alleged tactics included attempting to pressure people to sell their land at a price determined by OceanaGold and threatening legal proceedings against illiterate farmers – allegations flatly denied by OceanaGold.

Oxfam Australia called on the Australian mining industry and parliament to establish an independent complaints mechanism to help resolve complaints from communities affected by Australian mining operations overseas and avoid situations such as those that are now occurring in Didipio. “Until such a mechanism is established, companies such as OceanaGold should respond to community requests for independent oversight and assistance by institutions that have the trust of those local communities,” said Ms Martin.

— Edited, read the whole article at http://www.oxfam.org.au/media/article.php?id=447

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web