Hi everyone, thanks so much for coming today. It’s great to see you here. On a personal note, it’s really wonderful to be back in Brisbane, where I was born and raised, to share with you some of the amazing stories that have been very generously shared with me over the past few years.

First though, I’ll start with an anecdote – one that I think captures the theme of my recent book The Outsiders Within as well as today’s topic, ‘Crossing Cultures’. On the footpath near my home in north Melbourne where I currently live, I recently saw some stencil art that said “Don’t Tampa with Land Rights”. For me, it succinctly made the connection between keeping Indigenous insiders out and stopping outsiders getting in. And it’s this same mindset we see at work today in the Howard government’s recent winding back of land rights as part of its intervention in the Northern Territory, and its excision of a number of islands from Australia’s migration zone. The idea in both cases is to stop different cultures tampering with, or crossing with, the rest of us.

How much worse this threat to white Australia is when the two cultures most feared in the collective psyche – ‘Asians’ and ‘Aborigines’ – come together in cross-cultural unions!

The long history of Indigenous and Asian cross cultural union is the subject of The Outsiders Within, and these encounters have been going on since well before Captain Cook’s arrival. Anxieties about losing the land to migrant outsiders and Indigenous insiders are not new in Australia. Nor are the even more dire predictions about what might happen if migrants and Indigenous people were to join forces.

In fact it was 110 years ago when the Queensland colonial government was the first in the country to introduce legislation designed to prevent Aboriginal and Asian people from working together and from engaging in sexual relationships.

In 1897 Queensland introduced the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, and, as you can probably guess, the Chinese were firmly in mind with that policy. Farmers’ Associations, humanitarian lobbyists and others argued that Aboriginal people needed protection from the unscrupulous Chinese who were using opium to keep Aboriginal workers in their employ. But their concern was less that Aboriginal people might become addicted to opium and more that they might be attracted to work for Chinese employers rather than Whites. A 1901 amendment to that original 1897 Act made it illegal for any Chinese people, whether merchants, market– gardeners or shopkeepers to employ any Aboriginal workers. This was a real blow for the local Aboriginal community because the Chinese usually paid their Aboriginal workers higher wages and treated them much better than their Anglo-Celtic counterparts. The 1901 amendment also made it illegal for Chinese people and all other so–called ‘Asiatics’ to marry an Aborigine without first getting written permission from the Aboriginal Protector. White men were also caught up in this legislative net, but as a general rule they found it a lot easier than Asians to get the permission of the Protector.

This long history of cross–cultural encounters between Indigenous and Southeast Asian communities that I’ve just so briefly sketched, is largely missing from ‘the Australian story’ – it’s certainly not taught in schools. Forgotten too are the legalised efforts of successive white governments to police, marginalise and outlaw these cross–cultural communities. These have been written out of history even though local governments, Aboriginal Protectorates and police in Queensland, followed by Western Australia and in the Northern Territory and in north western Australian places where the pearl-shelling industry played a prominent role, went to extraordinary lengths in order to prevent the so–called ‘cohabitation’ of Aboriginal women and Asian indentured labourers.

In each of those states Aborigines and Asians were to be kept well apart. Indigenous-Asian couples endured midnight raids in their homes. Aboriginal women were even chained to trees to prevent their associating with the Asian crews while their pearling luggers were moored nearby. Couples who dared to love against the law risked the fining, imprisonment and deportation of the men and the removal of Aboriginal women and children to remote reserves and missions.

These are some of the stories told in my book and the question then as now is: WHY? Why would we go to such lengths to stop encounters between the communities? I’ll just share a couple of other short anecdotes that are in the book.

In one family’s case a removal order was sent for a ‘mixed–race’ child of Aboriginal–Chinese descent who was classified as a so–called ‘half–caste’ and therefore came under The Act. He was found to be living with a Chinese person – his biological father. The removal was prevented only because a local constable stepped in and vouched that the child was not neglected. In another case, an Aboriginal-Chinese man was for some reason deemed to be European, and not Aboriginal. He was thereby exempted from The Act. But he came into trouble with the law for engaging in a sexual relationship with his Aboriginal partner. Either way it seems he was caught.

Another family experienced anti–miscegenationist sentiment crossed with war-time paranoia. An Aboriginal woman [the daughter of an Aboriginal mother and Filipino father] was interned with her Japanese husband and their children at the outset of World War II. When her husband’s status – like that of all other Japanese pearling lugger crews – was changed from internee to prisoner of war, he was sent off to be imprisoned with captive troops, but she was forced to remain behind in detention with four of their children to look after, not knowing when they would be released. Stranded apart from her husband and extended family, subject to the accusation of abetting the enemy cause – her letters to her husband were chemically tested and read for any sign they contained secret information – her mental health deteriorated after a few years. She was then put into a mental institution and her children were removed to a convent many hundreds of miles away. Extraordinary!

I come back to that question again: Why did the phenomenon of people of different cultural and racial backgrounds brokering social, personal & commercial alliances fill the colonial and federal authorities with such horror? And why are these chapters missing from the Australian story? I’ll leave that question hanging and hope you will read The Outsiders Within to find out.

One of the main points I make in the book is that it’s not a standard history. I also look at artistic and cultural production that has come out recently. An extraordinary range of work by a number of Indigenous and Asian-Australian artists, writers, performers and musicians. And even though their history has been largely left out by White Australian historiography, they’re putting their stories out there and we just have to listen and learn from them.

These stories are so exciting in their own right. They are stories about suffering but also show people’s immense capacity and courage to overcome obstacle. They are fascinating because they are often beyond the book — they might be visual arts projects, photography, or performance — and they are not voices that come to us from the archive, they’re the voices of the people themselves.

I find them really exciting and challenging because unlike the White Australian version of events which is often, at least in its mainstream, the sanitised and whitewashed and very triumphalist success story that we are often told. These stories tell it like it is, and make it very clear that relationships between Aboriginal & Asian people were sometimes less than harmonious, that Aboriginal and Asian people were positioned differently on the social pecking order, and that from an Indigenous perspective, Asians might even be seen as another set of invaders who used Aboriginal labour, land and waters for personal gain. People like the Pigram Bros, Jimmy Chi, Alexis Wright, Andrish Saint Clare, William Yang, Hung Le, Lucy Dann and others insisting on the irreducible complexity of living together.

These are not just black and white stories, the kind of story we usually get. These stories challenge us to acknowledge that you don’t need racial and cultural homogeneity to create functioning communities, that we don’t need to all be the same to live as one. And this is the challenge that the stories in this book extend to all of us. But I wonder really how well we are responding to this challenge. To judge from the work that I’m doing now towards my second book, which will be on Indigenous Australians who have embraced Islam, I really think that perhaps we have a long way to go in learning how to embrace cross-cultural identities.

I was recently interviewed for an article in The Sydney Morning Herald in which I stated that I felt Islam had played a very positive role in a number of Indigenous people’s lives — those people who had embraced Islam and decided to become Muslim. A very conservative Melbourne-based journalist wrote quite discouraging comments on his blog, and then there were a number of people who posted responses, and the paranoia in those was really quite startling. They characterised Muslims as bloodthirsty, murderous terrorists and connected this to the idea that Aboriginal people, who they were at pains to point out already have control of land that us, non-Aboriginal people aren’t permitted to enter, would, with the help of these Islamist converts, probably get control of even more of ‘our’ land. It appears now that perhaps the ‘outsiders’ that we’re most anxious about, have changed from Asians to Muslims. But, it’s still obvious to me that their cross-cultural connections with Indigenous people are still arousing the same paranoia.

In keeping with today’s theme, I’m going to be talking about two kinds of migration — two types of migration that are not usually discussed together. The first is the more typical form of migration we are all familiar with – the migration to Australia of people from foreign shores. The second kind of migration I will refer to – and we’ll discuss later how these two are intimately connected – is an enforced internal migration, where people are taken from familiar to foreign places inside Australia.

It was actually Pauline Hanson who first led me on my journey of considering how these two forms of migration, that from outside Australia, and the other a form of exile within, are connected – the journey that led to my writing of The Outsiders Within. And since we are in the home of Hansonism, this is the perfect place to share this story with you.

As you will no doubt recall, until recently when she added Muslim communities to her long list of Australia’s least wanted migrants, Hanson targeted that nebulous group called ‘Asians’. Besides being concerned that we were about to be ‘swamped’ by Asians, she castigated them for ‘refusing’ to speak English, for ‘daring’ to live in ghettos, and for their ‘failure’ to assimilate. Her other main political target though, was Indigenous people. She argued that they were costing hard–working taxpayers money because of their receipt of social security payments and other so-called ‘special benefits’, “no matter how minute the Aboriginal blood.”

Unlike Hanson, I had never really considered Aborigines and Asians together. I largely thought about Australian history as an encounter between Indigenous and Anglo–Celtic people on the one hand, and as another encounter, unfolding more recently, between white settler and Asian interests. I hadn’t really considered them in the one story. What did Hanson see that I didn’t? Was there a long history that I didn’t know about, of engagement between these two communities in Australia? And, if so, had white Australians always been anxious, paranoid even about them in the way Hanson appeared to be? The extraordinary stories I uncovered in writing The Outsiders Within provided a resounding YES to both questions.

Hanson did not so much introduce, as articulate the racism and resentment that many of her voters were already feeling. She exploited widespread, if politically submerged, anxieties about Indigenous Australians as the internal ‘Other’ and Asians as the external ‘Other’. Indigenous Australians, intent on getting back their land, were effecting a kind of invasion from within, while Asians, who were just as intent on taking the country, were invading it through unchecked migration. Hanson had, no doubt unwittingly, articulated the very dis–ease at the heart of the white Australian imagination, which, unable to confront its own illegitimate beginnings and colonial theft, always fears what it has taken can be taken away.

The fear of outsiders within, whether coming from outback Australia or from Asia’s teeming hordes, is nothing new. My book tells how 100 years before Hanson’s rather dramatic entrance onto the political stage, other Queensland politicians were voicing their concerns about precisely these communities, largely with reference to the burgeoning pearl–shelling industry in the Torres Strait. In fact Queensland was the first state (closely followed by Western Australia and then the Northern Territory) to introduce legislation designed to prevent Aboriginal and Asian people from engaging in working and sexual partnerships.

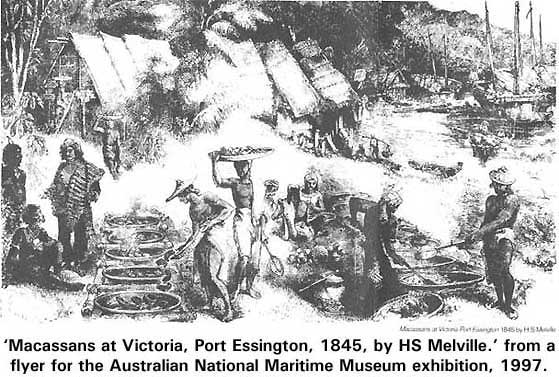

The exemption of the pearl–shelling industry from the so–called White Australia Policy saw the arrival of thousands of Asian indentured labourers each year in places like Broome, Darwin and Thursday Island. The men came from Japan, China, Indonesia, West Timor, Singapore, the Philippines and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. In the absence of Asian women, the indentured labourers readily entered relationships with Aboriginal women. But to those seeking to engineer Australia’s racial and social identity, these so-called ‘immoral’ unions were to be stopped at all costs. The reasons given were that they led to increases in venereal and other diseases, it also meant that Aboriginal women were not available for the sexual satisfaction of white men and, perhaps most horrifying of all, they led to an increase in the number of so–called ‘piebald’, ‘mongrel’ or ‘coloured’ children who, it was feared, might outnumber and swamp the white population.

It is important to remember that when these policies were introduced in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the north and north-west of Australia were thinly populated by whites until the post–World War II period. Asians not only represented a territorial threat and sexual competition, they were also an economic threat – particularly when they employed Aboriginal workers. This raised the ire of local farmers and station managers who found it difficult to keep Aboriginal workers in their employ. If Aborigines worked for Chinese market gardeners, Japanese shopkeepers and other Asians, they would be unavailable for white economic endeavours and, at the same time, would contribute to the material success of Asian businesses.

These are just some of the arguments the politicians used to justify their introduction of legislation designed to keep Aborigines and Asians apart. But I became very interested in the symbolic issues at stake. What did Indigenous and Asian people represent in the white Australian imagination? What fear was at the heart of the government’s strident attempts to separate Aborigines and Asians? My book suggests that these policies of separation were the legal expression of a constant anxiety about the land being taken away.

Here’s how it works. In justifying their unlawful expropriation of Aboriginal lands, white colonists or invaders insisted that the land was empty and there for the taking. In order to maintain this lie and deny the presence of the Indigenous people, colonists introduced the legal dictum terra nullius; they murdered Indigenous people; tried to forget about them by packing them off to remote reserves and missions, or by writing them out of Australian history altogether. And when all of that didn’t work they tried to make Indigenous people disappear by assimilating them and turning them into white people.

This belief in the myth of Australia’s emptiness led inexorably to the widespread fear that someone else might come and fill it up. The fear, if you like, of the invader being invaded in turn. Anxiety about the arrival of unwelcome outsiders intent on becoming insiders, went hand in hand with another sustaining myth of Australian national identity – that Australia is isolated. It is isolated of course from Britain, but not isolated from Asia, as we all know and as white colonists were acutely aware of at the time.

And here’s where we come back to our two forms of migration. On the one hand the state looked outward, attempting to prohibit the migration of Asians altogether, or when expediency dictated otherwise as in the case of the pearl–shelling industry, to at least manage and control how they migrated here. Asian pearl–shellers arrived here as bonded or indentured labourers. They had little power over the terms of their labour contracts and were obliged to remain working in the pearl–shelling industry for the period of their indenture. Local governments and the pearling masters wanted the Asian migrants for their labour only. They did not want them forging societies or creating a sense of community.

And to prevent this they created another whole class of people who were internally exiled. The state and federal governments did not just look outward, they also turned their segregating gaze inward, controlling the movement and marriages of Indigenous people. In a sense then, one kind of migration precipitated another. The migration of Asians from foreign shores led to the internal migration – or perhaps exile is a better word – of Aboriginal and Islander people. As punishment for committing the crime of engaging in relationships with Asians, many Indigenous women and their Aboriginal–Asian children in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, became involuntary migrants — people sent away from their traditional country, language and kin, to live in exile in foreign places on remote reserves and missions.

Territorial anxieties about the land being taken away are still with us. It is no accident that the government has recently made such strident attempts to prevent asylum seekers, refugees and other so–called ‘queue jumpers’ from entering and gaining a foothold in Australia. Asians, the more traditional source of anxiety, have now largely been replaced in the white imagination by others from different foreign shores, but the concern about losing the land to outsiders remains unchanged.

Nor is it a coincidence that the government’s recent intervention into Northern Territory Aboriginal communities has included attempts to further diminish Aboriginal people’s rights to their land and abolish the permit system that regulates access to Indigenous communities. I think these two things — keeping refugees and migrants out and trying to wind back native title — are all more steps in another long line of strategies designed to guarantee white unilateral possession of the nation and are all done to deny our own migration here from foreign shores.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web