This perspective has not changed much. Australia’s story of the Pacific is of progress and romance, of journeys and new beginnings. This is Australia’s welcome mat to the world. The nation still faces the Pacific. This mental alignment east has not changed since the beginning of white settlement. Neither have mental perceptions of Australia’s seas to the north. On the opposite side of the continent, at the nation’s ‘back’, lie the Indian Ocean and its sibling seas, the Timor and Arafura. These are the nation’s backwaters, remote and foreign. They border Asia. When Billy Hughes, the Australian war prime minister, declared in 1919 that the nation was a tiny white drop in a coloured ocean, it was the ‘yellow seas’ of the north that his words implied in the minds of his public. These waters, like the region they framed, harboured menaces and contagion. They promised distance and partition, but they also threatened danger to the exposed, soft underbelly of the White Australia ideal.

In the past ten years or so, there has been a strong revival of the yellow peril anxieties invoked by Australia’s northern maritime borders. The attempts by refugees to voyage by boat via the Timor and Arafura Seas to Australian waters have also been consistently described by journalists and politicians alike, as an attempt to come in the ‘back door’. As recently as 2004, government senators repeatedly invoked the spectre of ‘thousands of people’ coming illegally to Australia, ‘in through the back door’ to quote the Immigration Minister Senator Amanda Vanstone.(3)

The metaphor of the back door is a powerful one in the Australian psyche. ‘The back door had a sort of tyranny’, wrote Robert Drewe in The Shark Net. ‘At the front door the householder was in charge, in a stronger position to decline what was being offered … While the front door was public, the back door was more intimate. The caller was almost over the threshold. A back-door caller couldn’t be seen from the street’.(4) More than ever, these waters have come to represent the nation’s vulnerability in the public imagination, a gaping, unguarded back fence, despite the fact that it has become the most militarised border in Australian history in recent years. The nation spent these final years looking backwards over its shoulder, constantly warned to watch its back. It was the fear of being caught unawares from behind that drove these waters into the frontline of national security concerns.

The idea of these waters as somehow threatening and dangerous was also reflected in the nation’s media headlines, describing the unprecedented numbers of refugees travelling via these waters in terms such as ‘tidal waves’, ‘tsunamis’ or ‘rising tides’, almost as if, by extension, the ocean itself was about to rise up and overcome the fragile boundaries of the land, just as the refugees were depicted as threatening to tear away at the social fabric of Australian society.

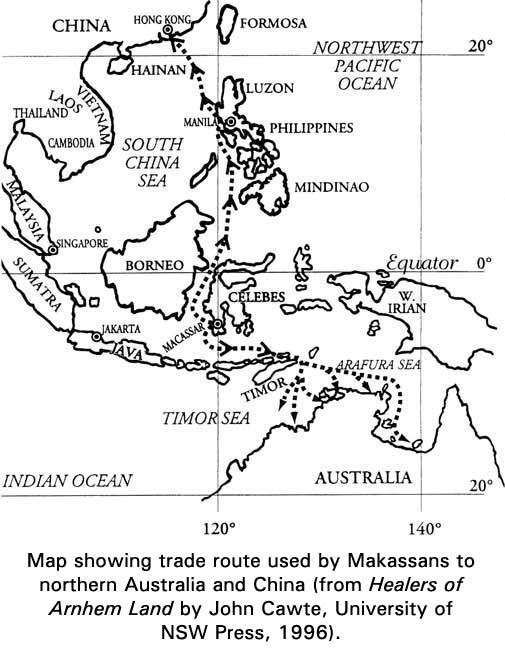

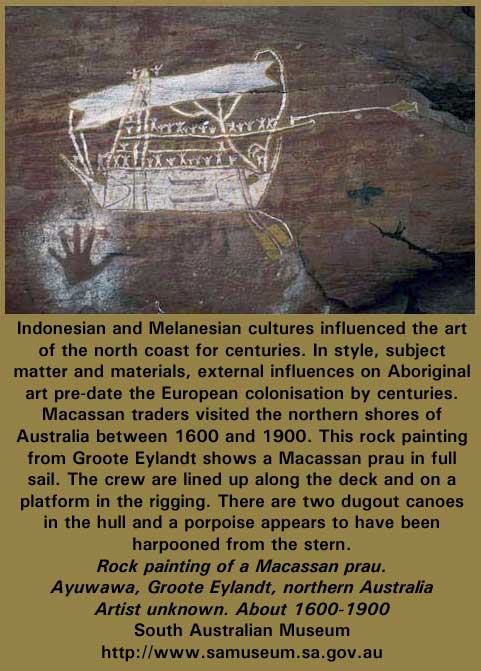

Although the fleets of Macassans stopped coming in the early twentieth century, the men who had crewed them did not. Indonesian fishermen, often the same men who had worked the Macassan fleets, continued to make these journeys as they had done for centuries, searching for marine produce to trade on the Asian market through the port city of Macassar. They came in small single boats, known as “perahu”, sailing the reefs and islands of the Timor Sea by the night stars, the winds, currents and the cloud patterns as their navigation tools to fish for trochus and trepang to trade on the Chinese market through Macassar.

This history of maritime contact with Asia continued right through the twentieth century, and marked coastal relations onshore as well. Australia passed its Restricted Immigration Act in 1901 — aptly known historically as the White Australia Policy — that effectively barred any persons of non-European background from entering the country. Meanwhile Broome, the booming pearling town in the northwest, was busily shipping in men from all over southeast Asia to work on the pearling luggers, something it continued to do for the next few decades, even as Asian labourers were being summarily shipped out of other parts of the country. It took two Royal Commissions, but pearling eventually became the only industry to gain exemption from the Act. Senator Staniforth Smith, visiting the town in 1902, remarked that a visitor might be excused for thinking that a part of Asia had been detached and grafted on to the Australian continent: ‘Superficially, if not actually, one has left our very English Australia and has already crossed the small stretch of sea separating us from the rest of Asia.’(6)

Australia’s relationship to its seascapes is complex. It has invested deeply in the construction of its identity as an ‘island nation’, and in so doing has inscribed fears, desires and the myths of nationhood into its sense of geography, both maritime and terrestrial. There are many seas in the Australian psyche, and not all are considered equal. But it all depends on whether you are looking out at the world from the front door or the back door.

Notes

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Search the SPAN Web