KASAMA Vol. 19 No.

3 / July-August-September 2005 / Solidarity Philippines Australia

Network

The Life of Street Children in the Philippines

and

Initiatives to Help

Them

The following are extracts from the testimony to the U.S. House Committee on International Relations by Fr. Shay Cullen, mssc, founder and president, People's Recovery Empowerment Development Assistance (PREDA) Foundation, Inc., Philippines.

September 13, 2005

Dear Honorable Members:

Last week before I left the Philippines to come here, I was working

with street children. One particular group led by a

Filipino–American street boy lives under a bridge abandoned

by their parents and society. They are addicted to sniffing industrial

glue to ward off hunger and they suffer malnutrition, parasites, and

live in fear of police beatings, arrest and detention without trial in

dehumanized conditions.

They are typical children of the streets, vagrants and in some other

cities, such as Davao in Mindanao, they become victims of shadowy death

squads that act with impunity in executing the teenagers leading us to

believe they are government sanctioned. The silence and inaction of the

authorities despite the mounting death toll is for us a sign of

approval. When we protested the killings some years ago we were sued by

the city mayor for defamation, but won our case when we proved

we were merely defending the human rights of the children and freedom

of speech on their behalf. We have been harassed, threatened

with death and brought to court to be deported for working to protect

the street children and defend their rights to experience childhood and

not to be abused.

Street kids are considered pests by some of the business

community—as vermin to be exterminated. But they have

committed no crime and are the victims of the wrongdoing of uncaring

and corrupt politicians and abusive, impoverished parents.

According to UNICEF, an estimated 100 million children worldwide live

at least part of their time on the streets. In the Philippines, a

government report in 1998 put the figure at 1.2 million street

children—about 70,000 of them in Metro Manila alone. Another

report estimates that there are approximately 1.5 million children on

the streets working as beggars, pickpockets, drug abusers and child

prostitutes (ECPAT). Today, the number of children and youth living

part of their lives on the streets in the Philippines could reach two

million out of a total population of 84 million.

This is the result of human neglect, spiritual paralysis,

greed and political irresponsibility that allows and exacerbates the

entrenchment of poverty in an unjust social system. The Philippines is

a fractured democracy, where feudal practices persist and where the

greater national budget is dedicated to servicing foreign debt and

paying a bloated bureaucracy, or is wasted on fake or overpriced

development projects. There is very little for social programs. We

believe that foreign aid is wasted when poured into the coffers of rich

politicians for projects they design to benefit their own family

businesses or those of their cronies. Even disaster relief money is

squandered and dissipated through corrupt practices.

Homes and shelters for street children are urgently needed. We are

trying to establish more. When we requested last month the use of a

government building constructed with relief funds given for the victims

of the volcanic eruption of Mount Pinatubo (and soon

abandoned), we were told it was better used for

officials’ offices and vehicles.

Advocacy and public awareness is achieved by workshops and training

seminars on the rights of children that PREDA gives to members of the

government, the public, students and teachers. The police and

prosecutors are specially targeted audiences, as they inflict the most

harm on children. The training and awareness–building

sessions teach as many as 11,000 people every year.

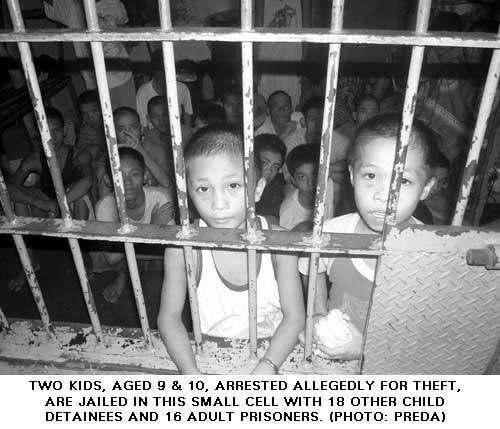

Street children are always hungry. They leave home hungry and beg on

the street where they are vulnerable to sexual exploitation, disease,

malnutrition, illiteracy, abuse and trafficking for sexual

exploitation. Most male street children in the Philippines are in

conflict with the law at some time and as many as 20,000 see the inside

of a prison cell, where they are mixed with pedophiles, drug addicts,

murderers and rapists. The street children are exposed to HIV/AIDS and

tuberculosis in the prisons.

One of the street children we are helping is a

14–year–old boy I call Francisco. He is a

Filipino–American living on the streets — abandoned

like many others when the military bases pulled out in 1992 and

thousands of children were left stranded.

All support ceased and many children fathered by American servicemen

became street children. We filed a class action suit in 1993 on their

behalf in the International Court of Complaints here in

Washington, DC, to establish these Filipino–American

children’s rights to assistance. They have been consigned to

live on the streets in hovels or slums in unimaginable poverty. Our

case did not prosper. The court ruled that the children were the

products of unmarried women who provided sexual services to US service

personnel in Olongapo, Subic Bay and Angeles City and were therefore

engaged in illicit acts of prostitution. Such illegal activity could

not be the basis for any legal claim.

Through the PREDA Foundation we are doing all we can for the street

children, the Filipino–American kids and those street kids

put in jail, where they suffer the worst punishment of all for a street

child—the unjust deprivation of freedom. Thousands of street

kids are behind bars for petty misdemeanors and no other crime than

being homeless on the streets, taking food without paying to ease their

hunger or, when no food is to be had, sniffing cheap industrial glue to

ease the pangs.

Solutions can be found in fair trade and by creating jobs for the

parents of street kids. This is one of our interventions to break the

cycle of poverty passed on from parents to children. Using our own

financial resources, we have saved hundreds of street children and

Fil–Am kids. Our funds come from PREDA Fair Trading, raised

from marketing the products from development projects PREDA has

established for the poor. The products are then exported and the

parents of street kids or those in dire circumstances are employed when

possible.

By providing direct service homes, feeding programs, street education

and advocacy to change the system, our work for children has continued

unabated and we have been able to save many from the streets, bring

them to a residential home, give values formation and formal and

non–formal education. Many have good jobs today. This work

still goes on. We have a home for former street kids who had been

imprisoned, some of whom were never charged and others were not found

guilty of any misdemeanor or crime. Some as young as eight and ten

years old.

We are asking that foreign aid assistance be focused, directed and used

to bring change in protecting the rights of street children, that World

Bank loans and ADB loans be more closely monitored for waste and abuse

and that child support programs be a component of every aid package.

WHO ARE THE STREET CHILDREN?

Street children are those children who, when they experience family

problems, hunger, neglect and domestic violence, escape from their

homes and live part–time on the streets. When they are

settled and know street survival techniques, they return at times to

their hovels and shacks to visit their families and bring food for

their younger brothers and sisters. When they see that the food they

bring is not enough, they return to the street and their brothers and

sisters sometimes follow them, looking for the source of the food.

Parents at times send them out to beg and scavenge and even prostitute

them or sell them in to bonded labor. We cannot forget the children

born of teenage street children and aborted in backstreet clinics.

Other street children are child workers, permanently on the streets and

engaged in scavenging, child labor, begging, peddling drugs and petty

theft. Many end up in jail. Their rights are frequently abused by the

police while on the streets. The girls are sometimes raped in custody

and forced to hand over their daily earnings.

Others are accused falsely for crimes committed by street children who

have been recruited into gangs controlled and protected by the police.

The gangs of street children prey on the younger and weaker children

and sometimes make them sex slaves, using drugs, food and fear to

control and dominate them. The street children are trained to be drug

couriers. Although innocent, the younger and unprotected can suffer

untold abuse by the other street youth. When in the jails, they can be

mixed with criminals, rapists and pedophiles.

They are runaways from dysfunctional, broken homes with an abusive

parent. In the home, usually a hovel and poor environment beside a

polluted canal or malarial swamp, they suffer sexual abuse, rape,

physical abuse, verbal battering, rejection, malnutrition, malaria,

diarrhea and dengue.

Most street children are illiterate. Having no incentive, money or

support and encouragement to study, they have dropped out of elementary

school. They join street gangs for their own protection and use

industrial glue as a mind– and mood–altering

tranquilizer. They work selling plastic bags, newspapers and flowers or

begging for a syndicate. Many are controlled by pimps and sold to sex

tourists on street corners or brought to the casa, a house of prostitu

tion. Street children are the poorest of the poor; they are the most

vulnerable and weakest and unless they are helped they will be the

HIV/AIDS victims of the future. They are forced to be child prostitutes

that attract foreign sex tourists. They are susceptible to becoming

criminals or even terrorists angry at the adult world that gave them

life in the worst misery imaginable. The adult world has done this to

the children.

GENDER BALANCE

The gender balance of the street children is roughly estimated to be

two–thirds boys and one–third girls. No exhaustive

research has been done to determine this. Based on the reports of

charity workers, this is a fair comment.

The groups of children are divided into those who live on the streets

permanently and those who live part–time on the streets but

go home every three or four days for a few hours or a day and then

return to the streets. They sleep in doorways, in push carts, under

plastic sheets, under bridges, in drainage pipes, in derelict

buildings, in abandoned cars and buses. Some even make shacks in the

trees along the fashionable boulevards. They favor being with the rich

dead in cemeteries where the tombs have roofs. They sleep in doorways

on the pavements or in the church porch. They live along the sea walls

and canals.

HOW YOUNG ARE THEY?

The children on the streets a few days a week are the youngest, from

seven to twelve years old. The older boys and girls on the street who

have been there for one or two years — that is, permanently

on the streets — are aged 13 to 16, although nine and

ten–year–old children are also in this group.

WHERE DO STREET CHILDREN COME FROM?

The unstoppable march of global materialism and economic domination

further enriches the elite and plunges the poor into even greater

poverty, increasing the number of street children and displaced

families. Poverty drives hungry farmers into the arms of the communist

rebels and the ranks of the Muslim rebels and other insurgents. They

recruit the children as child soldiers and expose them to terrible

dangers, violence and killings. These child soldiers are mentally and

emotionally damaged and flee the war for the streets. As the economy

worsens, poverty increases, political violence grows and more and more

impoverished rural families are driven from their homes in the

countryside because of an insurgency and rebellion.

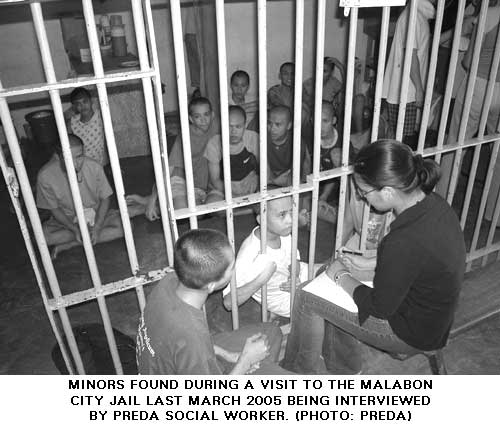

FROM THE STREET TO THE JAIL

Frequently arrested, street children are jailed without proper legal

procedures. They are at times treated as non–persons. In a

society where money is the measure of human worth, the children have no

value. In the subhuman conditions of overcrowded jails and

mixed with adults, they are deprived of light, learning, exercise,

family and companionship.

They are sodomized and sexually abused by adult prisoners in

overcrowded cells without even enough space to lie down together. Half

of the prisoners have to stand while the other half sleeps. The only

schooling the street children receive inside is how to be a criminal.

They suffer systematic violation of their human rights from the day

they are accused and are incarcerated without due process of law. When

they do get out, they return to the streets and are able to organize

street gangs of children to engage in crime. They are psychologically

damaged and traumatized and sometimes deranged. They face the dangers

of tuberculosis and other diseases while in the prison.

WHAT ARE THE INITIATIVES ON BEHALF OF

STREET CHILDREN?

COMMUNITY–BASED

The children are helped where they are — on the streets.

Street contact workers are trained to conduct non–formal

education and provide basic needs. Some are successful in getting the

children off the streets and into school. This project needs constant

follow–up, monitoring and financial support.

Street children themselves are sometimes trained to become street

educators themselves. They belong to the peer group and are respected

and accepted. They help to break down the lack of trust that street

children have of social workers and helpers. Maximum participation of

children in the work is a sign of best practice. Non–formal

education on the street is an indication of this.

JOBS FOR STREET CHILDREN

The children are helped to find income–earning activities to

support themselves on the streets, such as washing cars, guarding

parking areas, working as shine boys, selling products on the streets

and selling plastic bags around the markets. Sadly, some are made

professional beggars, drug couriers, pimps and child prostitutes.

EDUCATION

This is an approach that tries to bring responsive children into the

school system by providing support and encouragement and regular

follow–up and monitoring. Livelihood opportunities for

parents of the street children are sometimes provided by the project.

Thus the child becomes valuable to the family, as the child is a source

of financial assistance.

Drop–in centers for street children are common in the major

cities, but they are vulnerable to the children’s love of the

freedom they have on the streets. The dropout rate can be high. There

is the added difficulty of providing sufficient care that will make a

difference in the lives of the children. The centers provide basic

needs and shelter but the programs are usually short–lived.

When children do stay longer, they are referred to centers that provide

care for the long term. Residential live–in centers are

expensive projects and there are not many of them. Unless they are

placed in an area remote from the street and efforts are made to locate

and bring the parents into the process of helping the children, their

success rates will be low, as many children will be enticed to go back

to the streets.

FORMING SPECIAL ACTION GROUPS OF

STREET CHILDREN

The goal of these strategies is to help street children organize

themselves for self–protection and help. Some have been

successful. They feed each other, run for help to organizations like

PREDA in emergencies, bring medical help and in the past have even made

collections to pay extortion money to police to release their group

members. Today they call on PREDA’s legal officers to get

their group members out of jail.

STREET CONTACT FOR CHILDREN

This project entails regular contact by dedicated social workers with

groups of street children. The workers relate with the children to win

their trust, offer legal and personal protection against acts of abuse

by the authorities and work to release the children from jails and

holding cells or to get charges against them dismissed. The project

provides basic needs such as clothes, food, medical help and shelter

when needed. Efforts are made to contact parents and enable the child

to visit the parents. Part–time work for older children is

provided when possible.

Livelihood projects for parents are at times an aspect of street

contact, as are meetings, outings and non–formal education.

This model is being implemented by the PREDA Foundation, Olongapo City

and other agencies. There is no attempt to take the children off the

streets unless they are willing to enrol in school or agree to take

non–formal education courses.

The full text of this article and more information about what action you can take is available at the PREDA website

http://www.preda.org/home.htm or contact us here at SPAN.

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama