KASAMA Vol. 19 No.

3 / July-August-September 2005 / Solidarity Philippines Australia

Network

Education For Life, From Life:

Lessons to be learnt from a strong

indigenous tribe in the Philippines

The Aytas, the first native settlers in

the Philippines were thought to

have arrived some 30,000 to 70,000 years ago. They are from 25

ethnolinguistic groups scattered from Luzon to Mindanao. The over

80,000 Aytas who live in Mount Pinatubo have attracted interest because

of their preserved cultural identity. Sydney resident, DEBORAH RUIZ

WALL who has an interest in indigenous peoples, came to visit the Aytas

recently in Zambales.

‘LIFE–LONG

EDUCATION’

‘LIFE–LONG

EDUCATION’ was a catchphrase

that appealed to me when I was doing my training in education at Sydney

Teachers’ College three decades ago. For me, this meant: (1)

one never stops learning, and (2) education that has value is one that

has life–long application.

It wasn’t until April 2005 that I came to witness how this

basic educational philosophy is being used in effect to

re–construct the foundation of a society whose ancestry in

the Philippines goes back some 30,000 to 70,000 years.* This

realization came to me after I visited my indigenous Filipino friends,

the Aytas, in Central Luzon. During my visit, they happened to be

holding the first Assembly of the Paaralang Bayan ng mga Ayta ng

Zambales (PBAZ) or Folk School of the Aytas of Zambales.

‘Self–determination’, another

catchphrase, came to life for me when I saw how the Aytas are applying

their learning to determine their own future in a fast changing global

economy.

I first met Aytas in 1985 as part of an exposure tour with Australian

Teachers Federation members visiting the Philippines hosted by the

Philippine counterpart union, the Alliance of Concerned Teachers. In

1985, the year before President Marcos’ government was

toppled, our group went to Davao, Bataan, Samar, and Botolan. Our

tour’s focus was education but we were also given a broad

sketch of Philippine society and economy.

It was in Botolan, Zambales where I first came across Aytas. Zambales

is a province in Luzon Island north of Manila. We went to a village

called Masikap, and stayed in one of the Aytas’ huts. When we

arrived, one of my companions had a fainting spell. No one knew what to

do because we were far away from ‘civilization’.

The tricycle driver had gone and would not be back till the morning. In

those days, there were no cell/mobile phones for instant communication.

Anyway, one of the Aytas came and since I was the only Pilipino

language speaker, I was asked if the Australians didn’t mind

if they used their local healing method to treat our companion, a

Principal from Adelaide High School. The husband of the woman asked me

if I thought that was all right. I said that it wouldn’t do

any harm. So their healer came with a branch or two, chanted and rubbed

my companion’s knees and legs, and immediately, colour came

back to her face, as though she came back to life. She rose from the

wooden bench where she was lying looking half dead, and was herself

amazed at her instant recovery.

In the Philippines, people either go to a qualified medical

practitioner or to a ‘hilot’ (local healer), or to

both. The following morning in town, my companion asked a practitioner

trained in Western medicine to look at her knees and leg, but he

couldn’t find anything wrong and suggested an x–ray

if she was still concerned. “No, thank you,” she

replied thoughtfully. We noted the link between health and education as

an issue. Apart from this incident, it occurred to us that indigenous

people in Botolan had much to share about their healing techniques and

their local herbal medicine.

Most interesting was the literacy program for Aytas sponsored by a

missionary order. Sister Fe Villanueva gave us a briefing on their

program in Masikap Village which was a mirror image of how mainstream

schools taught literacy. We were tactfully informed by our guide that

another nun up the mountain used a different approach. It was different

because the literacy program was taught not only from the

Aytas’ cultural and linguistic background but also from a

holistic context: which included understanding the

socio–economic environment in which they live.

With lowlanders, the Aytas traded their fruit and vegetable produce

from the mountains. Their lack of literacy and numeracy meant that they

were most often cheated by middlemen and traders. We were exposed to

two different education approaches: one distinctly assimilationist; and

another which contained the seeds of political and economic awareness

and the possibility of self determination. Upon our return to

Australia, participant teachers on the tour gave talks around Sydney,

Brisbane, Melbourne and Adelaide about the result of our exposure.

My re–acquaintance with the Aytas took place in 1999 when

three young Aytas came to Australia on a tour to link up with other

indigenous groups and share their stories. I was living in Redfern,

inner city Sydney at the time doing research about Aboriginal and

non–Aboriginal reconciliation in an urban setting as part of

my Graduate Diploma in Ministry (Theology) with the Sydney College of

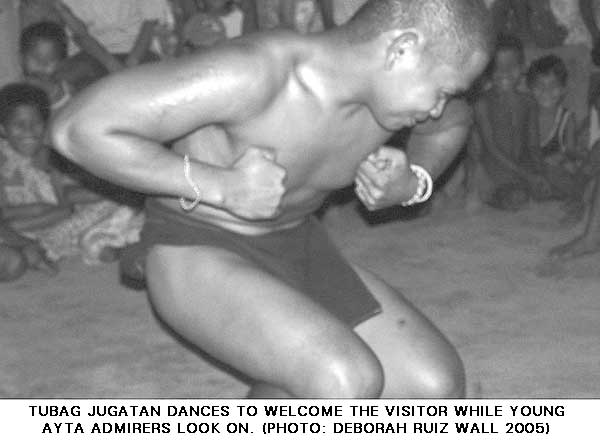

Divinity. The three Ayta visitors were: Epang Domulot, Orosco Cabalic

and Tubag Jugatan – ages 15, 17, and 19.

During their visit to Australia, they were accompanied by Sister Carmen

Balazo of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary (FMM). Sister Carmen,

known as Sister Menggay, provided support to the Aytas’

commitment to self determination and self reliance through introducing

a liberating educational pedagogy. This pedagogy is the Paulo Freire

method of teaching literacy and numeracy with a social context. What

was fascinating about her approach was: she did not proselytize.

Sister Menggay’s religious order was meant to complete its

task with the Aytas in 1992 but Mount Pinatubo erupted in 1991 and the

Aytas had to go down from their mountain home to lowland resettlements.

This was very disruptive because this particular Ayta group, who stuck

together under their banner of ‘LAKAS’ (an acronym

which collectively means ‘strength’), had to deal

with government officials, told where to go and what to do and would

have had to merge with other Ayta groups who did not have the same

holistic orientation in their training.

LAKAS wanted to return to their mountain home after the eruption, but

that was impossible. The place was covered with volcanic ashes (lahar).

Sister Menggay through her initiative was able to secure adequate funds

to purchase a block of land in Bihawo, Botolan to keep the community

together. This did not happen without a struggle, but eventually LAKAS

made it. They began by planting trees around the bare 7.5 hectares of

land and built their huts for the 155 families that live there now.

They also began replanting the mountain, no matter how challenging, on

47.5 hectares of land which LAKAS does not legally own but is under

their stewardship.

Is this a land rights issue? There was no land title system thousands

of years ago. The government recognizes indigenous people’s

‘ancestral domain’ but what this means in terms of

land rights and usage is not entirely clear. A land development plan,

for example, still needs to be drawn up. Recognition is a first step,

and the rest of what this means in practice is a process that needs to

be worked out.

SOME BACKGROUND ABOUT LAKAS

LAKAS stands for Lubos na Alyansa ng mga Katutubong

Ayta ng

Sambales or Negrito Peoples Alliance of Zambales. Formed in 1984 with

45 members from 12 sitios of Barangay Villar and Maguisguis, its main

activities were: literacy classes, cooperative building, and training

on the rights to ancestral domain. It became a Federation in 1985 and

was registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1987.

It has been six years since the Ayta Youth visit to Australia, and now

I was their visitor. The community gave me a welcome under their

wall–less public space. There were speeches and dance

presentations. It was a delight to watch very young Aytas do emceeing

and performing with hardly any inhibition. Such an inspiration, I

thought, for our public speaking classes at TAFE colleges.

At night I was taken to a guest house on the coast in the township of

Botolan belonging to another supporter of the community. The guest

house is a ‘bahay kubo’ – a nipa hut with

bamboo floors, very airy and comfortable as it was situated close to

the sea. The Australian Aboriginal circled–room layout for

gathering is equivalent to the Aytas’ wall–less

open space layout. The basic structure for a gathering is open space

under a roof, and posts planted in the ground or cement to hold the

roof. The place where we had dinner was a long table under a thatched

ceiling directly facing the ocean, so whilst I couldn’t see

the ocean then because it was a moonless night, I could hear the waves

and feel the sea air envelop us as we chatted and ate the fish, rice

and chicken adobo.

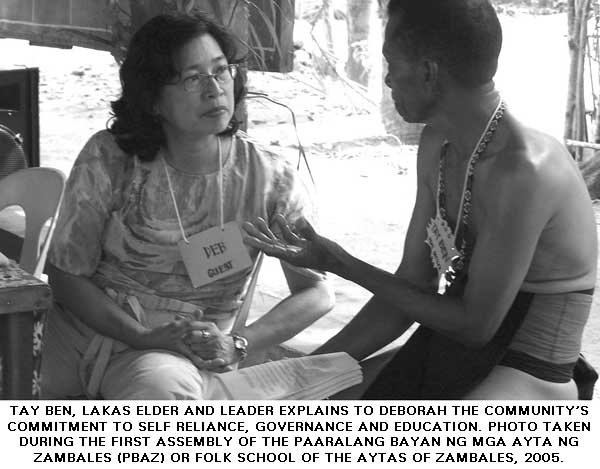

The following day was a big day for LAKAS. The first General Assembly

of Indigenous Leader Graduates of Paaralang Bayan ng mga Ayta ng

Zambales (PBAZ/Folk School of the Aytas of Zambales). PBAZ was formed

by the graduates of the Education for Life Foundation (ELF). Some Aytas

have travelled overseas to compare notes with folk school systems in

Denmark, Australia, Canada and the Americas. Some even had the

privilege of meeting Paulo Freire in person in Brazil.

THE FRUITS OF THEIR LABOUR

Some Aytas obtained top school achievements resulting in mainstream

school administrators altering their perception of Aytas. They are

beginning to feel respected and racist thinking and behaviour towards

them are gradually disappearing. They told me that local mainstream

schools are requesting Aytas to teach their folk dances at their

school. Non–Ayta farmers now also request Aytas to give them

training in organic farming and leadership. Respect and recognition of

indigenous skills and knowledge by the wider society help them regain

trust and confidence in their ability to deal with lowlanders on an

equal footing. Their experience shows that a

‘bottom–up’ approach to training can make

an impact.

The morning of the PBAZ Assembly was spent introducing the officers and

the guests (including me), and asking groups to give impromptu

presentations – to sing or dance. The afternoon was serious

business. It was intended to ask the Assembly to make amendments, if

required, and approve their Rules and Policies. Since PBAZ began, 123

Aytas had graduated from a six–week leadership training

course (four are deceased). The course is a prerequisite for membership

of PBAZ. Upon course completion, they can choose to exercise their

newly acquired leadership skills through the seven existing committees:

culture and literacy; health and sports; negotiation and advocacy;

research, documentation and evaluation; education, information and

training; livelihood; finance and membership. Folk education is

community rather than individual oriented. Graduates become aware of

their larger responsibility, and exercise leadership for and with the

community.

I spoke to a few of the guests: the Director for Distance Learning

Program, May Rendon Cinco and the local mayor, Rogelio Yap. I can see

that the aspirations of the Aytas are realized through their own self

determination and negotiation for support with NGOs (non government

organizations) like the Education for Life Foundation and the LGOs

(local government organizations) represented by the Mayor. The Mayor is

able to assist with infrastructure building such as provision of day

care centres, support for out–of–school youth,

irrigation and regeneration with planting 50,000 seedlings. On health

issues he is targeting elimination of tuberculosis and malaria. On

funding, he seeks joint venture projects with agencies such as Asian

Council for People’s Culture (ACPC).

From having hardly any educational opportunities before Sister

Menggay’s Paulo Freire literacy program, LAKAS today prides

itself with four university graduates, ten continuing university

students, and many high school and primary school children all

studying. The focus is not on money but on community building. People

who finish their degrees have to serve for two years within the

community, and when they start to work outside the community they are

expected to contribute a proportion of their income to LAKAS. If anyone

marries outside the community, they can only continue to live in the

community if their spouse believes in its ethos and is prepared to

abide by community precepts. Such measures are intended to ensure that

the strength of the community is not undermined.

COMMUNITY GOVERNANCE

Community Governance is what fascinates and impresses me with LAKAS.

Everyone from the age of reason is taught to make decisions

collectively and to practise leadership and negotiation skills. LAKAS

is very particular about moulding minds right from infancy and being

community– minded. There are categories of belonging within

the community: the very young (e.g. under six years), primary school

age, secondary school age, LAKAS youth, men, women, and the aged.

Decisions reached are consolidated at the community level.

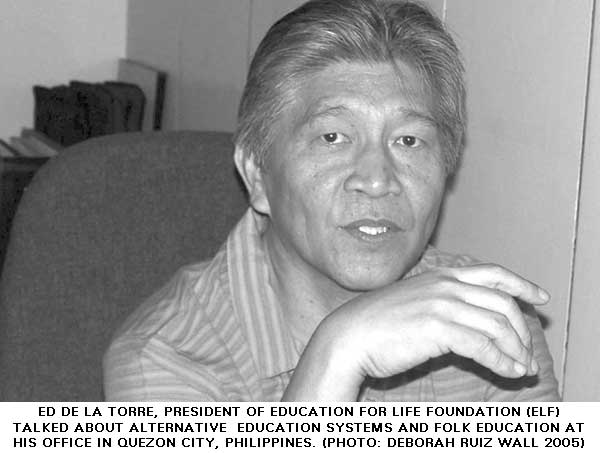

Back in Manila, I met Edicio de la Torre who used to be a Society of

Divine Word (SVD) priest and whose work on liberation theology I read

when I was doing my sociology thesis about church–state

relations. He is no longer a priest and is currently the President of

the Education for Life Foundation (ELF). ELF initially provided LAKAS

the 6–week leadership training course. LAKAS responded to the

challenge of conducting its own training based on a

train–the–trainer system.

Under President Marcos’ dictatorship, Ed was put in gaol for

nine years. Many human rights activists suffered the same fate. These

long years in gaol gave Ed the opportunity to think things through.

Upon his release from prison in 1986, he thought that while the people

had overthrown the dictatorship, much more needed to be done. Popular

democracy had to be rebuilt from the ground up. There would need to be

a new generation of leaders aware of their rights and ready to defend

them. They would need negotiation skills to talk to those holding

positions of power and influence. To flesh out his vision, he helped

establish the Institute for Popular Democracy (IPD). IPD wanted to

develop a comprehensive leadership formation program, which would not

only change poor people’s quality of life but include

everything that underpins sustainable and equitable development.

Ed discovered during a Popular Education Consultation in 1986 that many

people shared his vision. As a result of two conferences, a network

called Popular Education for People’s Empowerment (PEPE) was

formed. In 1987, Ed attended a conference at Hillerod Hojskole, a

school in Denmark, and found himself ‘staring at his

dream’: the folkehojskole (or folk school). He found that the

idea of a folk school was not new — the Danish in the 1830s

had a visionary, Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig.

Grundtvig’s country in 1783 was in a time of change.

Political reforms were taking place. Their national identity was

eroding, their monarchy was weakening, their self confidence was being

undermined by the loss of territory to Germany. Some of the people were

becoming extremely rich, but the majority were poor. The boy, Grundtvig

was searching for his own identity. Fortunately he was filled with folk

tales and songs of his Nordic tradition by his mother and another

elderly woman. He knew who he was, what his roots were, and where he

belonged. He dreamt then of helping his people remember their roots

through establishing an education for the poor majority, the almue

(root word: almuegjort or ‘made to be ignorant’).

During Grundtvig’s time, the almue were mostly farmers who

were excluded from any political decision–making. The folk

school he envisioned would be about life and teach purposeful living.

Through storytelling, poetry and song, students would learn about their

identity and cultural heritage. They would interact with each other as

co–learners. It would be an education for the whole of life.

It took 15 years for this vision to materialize. In 1844, The Rodding

Hojskole was founded by Christian Flor, a professor of the Danish

language at Cologne University. Other folk schools were founded later

in different parts of the country, and now, over 100 folk schools exist

in Denmark; 128 in Sweden; 93 in Finland and a few others in Iceland

and Faroe Islands.

And so it was in 1987 that Ed de la Torre sent word to IPD about the

folkehojskole and how such a school could be established in the

Philippines. In 1991, Ed was in the Netherlands. He and his partner,

Girlie Villariba wondered whether, with the help of the Danish, it was

possible to build a folkehojskole in the Philippines. At this time IPD

was experimenting with different leadership formation

programs. Ed and Girlie approached a funding agency, and the result was

positive. A proposal was put together within a few days which included

the result of village consultations with grassroots leaders as well as

with NGOs experienced in popular education. An alternative education

system was conceived with the twin aims of empowerment and sustainable

development rooted in the community. To encourage the folk school

project, the Education for Life Foundation was established.

Girlie Villariba and Marichu C. Antonio were ELF’s first

staff. With partnerships as their tools and ideas as their materials,

the school was built between 1991 and 1992. ELF’s NGO

partners were: the Institute for Popular Democracy which developed

the comprehensive leadership training program; the Philippine Rural

Reconstruction Movement’s program for sustainable development

and democratization in rural districts; the Cooperatives Foundation of

the Philippines, Inc which organizes cooperatives for the poor; the

Center for Urban Community Development which applies these concepts for

the urban poor; and Popular Education for People Empowerment, a network

of popular educators. With these partners, ELF was able to put up a

proposal to Danchurchaid. The proposal was approved, and the funding

was to come from the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA).

The next challenge was the process: how to implement this vision in the

Philippine context. It was decided to strengthen the local

organizations of the poor sections of rural and urban communities by

training their leaders. Before the six–week residential

formation course was conducted, there had to be a curriculum. Concepts

and themes were drawn up through informal discussions and formal

workshops with popular educators, development workers and activists

including specialists and resource persons. This phase of the program

was called pagbibinhi, or selecting seeds and growing seedlings. The

water to nourish the seedlings would be the philosophy of

‘education from life and for life’. The seeds were:

people’s empowerment, grassroots leadership, Filipino

psychology and culture, ethnicity, nationalism, popular economics,

tradition and rituals, gender sensitivity, pluralism, coalition,

learning to learn, learning to lead, learning from life and for life,

and negotiations.

ELF thought that a story–telling workshop where participants

share highlights of their lives and stories of their communities, their

values, tradition, the problems they face, and their leadership

experiences would be a useful preliminary workshop before participants

begin the course. This sharing would be documented and would become

part of their training material. This is truly ‘education

from life’.

And now ELF’s and LAKAS’ effort has borne fruit.

Graduates of the ELF six–week training course have now reaped

a new harvest and sown yet another seed: the formation of PBAZ

— a folk school for Aytas in Zambales in partnership with

LAKAS and ELF. Their goal in having their own school is to be able to

lift their quality of life and have a peaceful and progressive

community.

In formal schools, young indigenous people often face discrimination

and are discouraged from attending classes. In 2003, PBAZ conducted a

General Leadership and Alternative Learning System course. Topics

covered in the leadership training course included: philosophy and

process of learning, presentation of self and ideas, communication to

small groups, ecosystem, conflict management, leadership and

organization, leadership and empowerment, sports, Ayta culture, and the

Indigenous People’s Rights Act.

FOLK SCHOOL FOR AYTAS

More seeds can be sown from my meeting with Ed de la Torre. Already we

can see a sharing of experiences between indigenous peoples in

Australia and in the Philippines on life–long education and

alternative learning systems. Ed told me about ‘Biyaheng

Ayta’ (Aytas’ journey), a theatre group that

travels to various Ayta communities covering themes such as history

(elders) and youth (land and dance). Ed is interested to learn about

the process involved in certifying indigenous skills such as bolo

making or basket–weaving and other indigenous arts and

craftwork to give recognition to these practical skills and to ensure

that they are not lost.

In Australia, we have had some years of experience now in the

application of ‘Recognition for Prior learning’. We

also have an indigenous education system: Tranby Aboriginal Cooperative

College in Sydney and Nungalinya College, an ecumenical theology

college in Darwin. EORA Centre, an Aboriginal College, also exists

within the Technical and Further Education Commission in Sydney.

I see that indigenous people from Australia can benefit from seeing how

the whole–of–life education process and alternative

education system are applied by ELF and PBAZ in a rural setting. I see

that indigenous people from the Philippines can learn from the

challenges experienced in Australia in setting up an independent

indigenous–run educational establishment and how skills from

prior learning are recognized and certified.

Before becoming President of ELF, Ed held the position of Director of

Technical Education and Schools Development Authority (TESDA). TESDA in

the Philippines is similar to TAFE in Australia — a

government agency providing technical education and skills development

programs. It endeavours to work in partnership with local industry and

with people who need particular skills to gain entry into the job

market. Perhaps another joint venture is in the offing beginning with

sharing of experiences that would benefit both communities across the

seas.

It all starts from a vision, imagination, a dream. Seeds to be sown

from life, for life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

DEBORAH WALL was born

in the Philippines. She is

currently a member of the Executive Board of the NSW Reconciliation

Council whose aim is to propagate reconciliation between Aboriginal and

non–Aboriginal Australians

REFERENCES:

Padma Perez (1999) ELF Story Book: Paaralang Bayan, Paaralang Buhay,

Education for Life Foundation: Quezon City, Philippines.

Salinbuhay, from life, for life, August 2003 No 16.

*NOTE: The exact time of the first appearance of Negritos in the

islands is a contentious issue, but it is largely accepted that they

represent the most ancient prehistoric peopling of Asia going back as

much as 70,000 years. (see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negritos).

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama

Home | Aims and Objectives of Solidarity Philippines Australia Network | About Kasama